We listen to each other and to the Bible and the church’s constitution

By Jack Rogers

Every year the Presbyterian Church struggles with enormous moral questions.

In February 2002, as moderator of the General Assembly, I visited the Great Lakes Naval Training Center near Chicago. I met with the base commander — a two-star admiral, a woman and a Presbyterian. Her name is Ann Rondeau. After the usual pleasantries she asked me a penetrating question: “Are the churches discussing what constitutes a just war?” As Presbyterians wrestle with this profound question, it is helpful to ask how we as a body make such important decisions.

Presbyterians are not do-it-yourselfers. We make decisions as a community. This is a way of living out the Biblical notion that God has created a covenant community. We base our decisions on our traditional sources of authority and guidance — the Bible and the church’s constitution. We pray and seek the guidance of the Holy Spirit in interpreting these sources of authority. We listen to each other, believing that God speaks in the community of the church.

Our representative form of government puts significant responsibility on all members of the church. It is not easy to be a Presbyterian. We are continually called upon to decide whom we should elect and what side of multiple issues we should support.

For example, some denominations believe that Christians should always support the civil government, especially in matters such as war. Other denominations have an inherent suspicion of civil government and tend to withdraw their support from it. For Presbyterians it is always a judgment call. Like John Knox and five friends who produced the Scots Confession in 1560 (one of the 11 confessions in the Book of Confessions), we should obey the orders of “rulers, and superior powers … if they are not contrary to the commands of God.”

That big if is why we study things so much. We always need to discern what the will of God is and how it should be applied in complex situations.

Human limitations

Our Presbyterian predecessors in earlier centuries were keenly aware of our human limitations. For example, in the Westminster Confession of Faith, finished in 1647, we are reminded that “all things in Scripture are not alike plain in themselves, nor alike clear unto all.” Those things “necessary to be known, believed, and observed for salvation” are clear. However, “in all controversies of religion” the church needs to use scholarly study to help us sort out our differences. That requires us all to be patient with each other and do our homework until we reach some consensus.

The authors of the Westminster Confession of Faith did not exempt themselves from examination. They honestly asserted that “all synods or councils since the apostles’ times, whether general or particular, may err, and many have erred; therefore they are not to be made the rule of faith or practice, but to be used as a help in both.” We must prayerfully seek the guidance of the Holy Spirit and listen to one another in the church in order wisely to use the insights of our sources of authority and guidance. Neither Scripture nor confessions are rightly used when we pull sentences out of their context and make them into universal laws.

The Presbyterian way of making decisions looks a lot like the way the New Testament church made decisions as recorded in Acts 15:1-21. When there is a disagreement, we turn it over to a chosen group of representatives. In Acts those representatives were the apostles and the elders. They listened to expert testimony from those who knew the issue best—Peter and Paul and Barnabas. There was a lot of dissension and debate. People understood the Old Testament Scriptures differently.

In the end the apostles and elders discerned that a new thing was happening, the conversion of the Gentiles. They discovered that it was in accord with God’s plan as revealed in Scripture. Then they made some practical compromises so that the values of differing groups were honored. Their decision opened the door of the church to us.

Making decisions as Presbyterians is often a slow process that takes a great deal of work. Making decisions this way, however, usually yields wise judgments rooted in God’s revelation and our best human reflection. If we listen attentively to the Spirit of God, as we hear the greatest diversity of voices and earnestly seek to be faithful to the Bible and our constitution, we are as likely as humans can be to make good decisions.

Diversity is good

Presbyterians believe that the best decisions are made when the broadest possible representation of our diversity participates. We believe in the equality of all people before God, and therefore our system represents a parity, an equality, of persons. There are always both elders and ministers qualified to vote in every governing body. We seek to have women as well as men represented. We encourage people of every race and ethnicity to participate.

Slow progress

At times in our history we have been captive to a general cultural prejudice that prevented us from welcoming diversity. For example, from the founding of the Presbyterian Church in this country down into the 1950s we tolerated first slavery and then racial segregation in church and society. Until the mid-20th century the only persons voting in our governing bodies were white men. Several landmarks on the road to diversity:

1930 — Women are admitted to the office of elder

1956 — First woman is ordained as a minister of Word and Sacrament

1964 — First African American is elected moderator of the General Assembly

2002 — The PC(USA) becomes a member of Churches Uniting in Christ, a coalition of nine denominations that have committed themselves to the recognition of each other’s ministries. In the worship service celebrating this coming together members of the churches join in Holy Communion. The Episcopalians choose a bishop to represent them as a celebrant. The Presbyterian representative is an elder, a Chinese-American woman.

Decently and in order

When it is time to make a decision, Presbyterians do not just pull ideas out of the air. Our system of government enables an orderly process of discerning the will of God in which everyone participates. Here is an overview.

Government by the book

Presbyterians need to know and rightly use the books we rely on for authority and guidance:

Presbyterians need to know and rightly use the books we rely on for authority and guidance:

- The Bible

- The constitution of the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.)

The constitution consists of two books:

- The Book of Confessions contains 11 documents, dating from the 4th century to the late 20th century, that give us the main theological themes our ancestors in the faith found central in Scripture.

- The Book of Order gives us guidance for ordering our life as a community according to Scripture and the confessions. It sets out democratic principles of representative government and applies them to life in the church.

What Presbyterian government is not

● We are not episcopal, with government from the top down. In the Roman Catholic, Episcopal and United Methodist churches individual bishops exercise significant authority.

● We are not episcopal, with government from the top down. In the Roman Catholic, Episcopal and United Methodist churches individual bishops exercise significant authority.

● We are not congregational, with government from the bottom up. In congregational polity the local church’s decisions are final, with everyone getting to vote on everything. This is characteristic of Baptists and the United Church of Christ, among other denominations.

● We are not congregational, with government from the bottom up. In congregational polity the local church’s decisions are final, with everyone getting to vote on everything. This is characteristic of Baptists and the United Church of Christ, among other denominations.

Representative government

Presbyterian polity is representative government, very similar to the United States government. Authority flows both up and down. We elect representatives to make decisions on our behalf.

Presbyterian polity is representative government, very similar to the United States government. Authority flows both up and down. We elect representatives to make decisions on our behalf.

One difference in emphasis between our national and church governments is that the persons Presbyterians elect to represent them are expected to vote according to their consciences as they are informed by the Holy Spirit. They cannot be instructed by their constituency on how to vote, nor are they bound to vote in the same way as the majority of those who elected them.

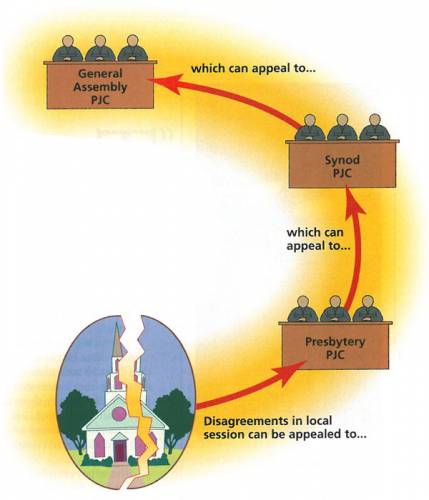

When we don’t agree ►

Presbyterians do not always agree with the decisions of their representatives. So we have a representative appeals process. There is a rising system of courts, called Permanent Judicial Commissions (PJCs). Disagreements arising in a local session can be appealed to the presbytery PJC. An appeal can be made from the presbytery to the synod PJC and from the synod to the Permanent Judicial Commission of the General Assembly. There is no appeal from the General Assembly PJC. Like the United States Supreme Court, its decisions are final. If there is disagreement with a decision of the General Assembly PJC, the recourse is to go back to the legislative system and make more specific laws to guide our representatives in the judicial system.

Presbyterians do not always agree with the decisions of their representatives. So we have a representative appeals process. There is a rising system of courts, called Permanent Judicial Commissions (PJCs). Disagreements arising in a local session can be appealed to the presbytery PJC. An appeal can be made from the presbytery to the synod PJC and from the synod to the Permanent Judicial Commission of the General Assembly. There is no appeal from the General Assembly PJC. Like the United States Supreme Court, its decisions are final. If there is disagreement with a decision of the General Assembly PJC, the recourse is to go back to the legislative system and make more specific laws to guide our representatives in the judicial system.

Ordination — not just for clergy

The principle of gathering diverse persons who are unified in their commitment to Jesus Christ yields a distinctive aspect of our polity. In most denominations only clergy are ordained. In the Presbyterian Church elders and deacons, as well as ministers, are ordained. Deacons are ordained to a ministry of service. Elders are ordained to a ministry of governance. Ministers of the Word and Sacrament are ordained to service and governance and also to a ministry of teaching and pastoral care.

The principle of gathering diverse persons who are unified in their commitment to Jesus Christ yields a distinctive aspect of our polity. In most denominations only clergy are ordained. In the Presbyterian Church elders and deacons, as well as ministers, are ordained. Deacons are ordained to a ministry of service. Elders are ordained to a ministry of governance. Ministers of the Word and Sacrament are ordained to service and governance and also to a ministry of teaching and pastoral care.

This article originally appeared in the April 2003 issue of Presbyterians Today.