Concern for refugees and immigrants unites area churches

by Gregg Brekke | Presbyterian News Service

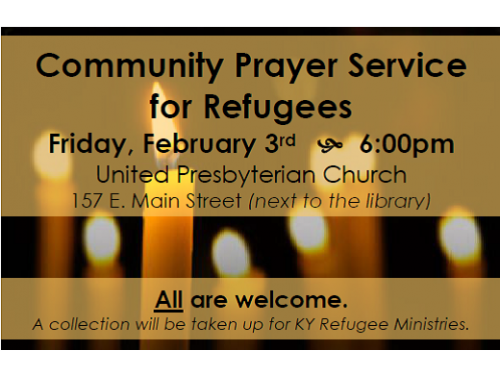

LOUISVILLE – The small town of Lebanon (pop. 5,800) sits 70 miles southeast of Louisville in the heart of central Kentucky. Surrounded by lush farmland, the area is known as a hub for bluegrass music, manufacturing facilities and bourbon production. It’s also home to United Presbyterian Church, which hosted a prayer service last Friday in response to President Donald Trump’s January 27 executive order on refugees and immigration.

LOUISVILLE – The small town of Lebanon (pop. 5,800) sits 70 miles southeast of Louisville in the heart of central Kentucky. Surrounded by lush farmland, the area is known as a hub for bluegrass music, manufacturing facilities and bourbon production. It’s also home to United Presbyterian Church, which hosted a prayer service last Friday in response to President Donald Trump’s January 27 executive order on refugees and immigration.

The February 3 event came about after the church’s stated supply pastor, the Rev. John Russell Stanger, read part of the statement issued by the Rev. Dr. J. Herbert Nelson, II, Stated Clerk of the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.), regarding the travel ban. That Sunday, Jan. 29, was just Stanger’s second Sunday as stated supply pastor with the congregation and he was unsure of how to introduce the topic that was on his heart. Yet, he felt it was important to read Nelson’s words before the prayers of the people.

“After that service, one of our ruling elders, Wendy Smith, came up to me and said, ‘I think we need to do something,’” he says. “My sense is the people of United Presbyterian felt there was a need, and that we were the church that could do this kind of service—and go out on a bit of a limb—and if people perceived this as being critical of the president or a particular political party, we could take that risk.”

In the days following the executive order, Stanger believes the people of Lebanon were looking for a “way to grieve” the closing of U.S. borders to those fleeing danger and “wrestle with what it means to speak out publicly when we do have Christian convictions about caring for the least of these.”

The implications of the travel ban weighed heavily on Smith and her husband as well.

“Early Sunday morning, around three in the morning, my husband and I were up talking about it,” she says. “We were pretty distraught and concerned, having heard the stories of families caught in the limbo.”

After the service, Smith talked with others in the congregation before approaching Stanger to see if a community prayer service could be organized. “That’s not something, I’ve ever done,” says Smith. “I’m not a prayer service-y type person.”

But the session [church governing body] and members were in agreement and Smith started the wheels rolling on arranging the service by calling a previous supply pastor, community members, Roman Catholic organizations in the county, and other area ministers, and representatives from Kentucky Refugee Ministries.

Between 80 and 90 people gathered for the prayer service. “For a community that worships with 30 or 40 people on an average Sunday, that was an incredible turnout,” says Stanger.

A number of Catholic nuns from nearby convents joined in the prayers, along with members of the local Catholic church, townspersons unaffiliated with a church, members of other Protestant congregations and two additional ministers.

“We read scripture, recited prayers, passed the peace and lit candles to carry out into the world,” says Smith of the simple service. An offering of over $1,000 was received for Kentucky Refugee Ministries and its continued work.

“My sermon that Sunday [January 28] talked about how the church doesn’t have the option of hiding our light,” he says. “And when a situation like this comes up there are all kinds of reasons not to do a service like that, but ultimately we have to live into our call that we have good news—that refugees are valuable children of God who deserve respect and safety. So hiding our light would be not to do the service out of fear, or being seen as too political, or that it would alienate people. But when we took the risk we saw that so many people came—even without a Sunday in-between to announce it in church.”

Stanger had moderated his first session meeting at the church the week prior to the issuance of the executive order, where he heard the session members’ concerns for the church. It had declined over time, wanted to grow and had a beautiful building that could welcome people in. “It’s kind of the story of the Presbyterian Church right now,” he says.

“And this opportunity [to host the community prayer service] came up in a really authentic way, where we had a Baptist minister and United Church of Christ minister help lead the service along with the Catholic attendees,” says Stanger. “There was a sense that we were doing something larger, that resulted in people visiting on Sunday morning, and having a sense that this is what the church believes in.”

Smith and Stanger say they were prepared to receive “nasty calls” about the service after it was announced in the local newspaper. “Our region is definitely ‘Trump country,’” says Smith of the central Kentucky area around Lebanon, adding the invitation to attend the prayer service welcomed people who had concerns for refugees, no matter how they voted in last year’s election. But the church secretary reported no negative calls and the service had no protesters present.

“Political or not, Jesus said some very specific things about how we’re supposed to treat others—how we’re supposed to treat the stranger and the poor,” says Smith. “Jesus couldn’t foresee our specific political situation, but he sure did speak to it.”

![]() You may freely reuse and distribute this article in its entirety for non-commercial purposes in any medium. Please include author attribution, photography credits, and a link to the original article. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDeratives 4.0 International License.

You may freely reuse and distribute this article in its entirety for non-commercial purposes in any medium. Please include author attribution, photography credits, and a link to the original article. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDeratives 4.0 International License.