Knox Presbyterian Church in Cincinnati takes a listen, learn and act approach to mitigate structural racism after it learns about the terms of a century-old gift that helped build the church

by Mike Ferguson | Presbyterian News Service

Leaders and members of Knox Presbyterian Church in Cincinnati have been working to end structural racism since learning a gift that helped construct the church a century ago was intended for white people only. (Mike Fitzer/180 Degrees)

CINCINNATI — Ever since discovering their church was built a century ago partly through funds donated “for the white race only,” the 1,200 or so members and the leadership of Knox Presbyterian Church in Cincinnati, Ohio, have worked hard not to duck the church’s history, but to learn from it and to, in tangible ways, reach out and make connections that make it clear where the church is headed during the next 100 years: ending the sin of systemic racism.

According to Knox’s pastor, the Rev. Adam Fronczek, nearly 100 years ago a woman left $22,000 — about $17,000 after legal costs, or about $258,000 in today’s dollars — to aid in constructing a Presbyterian church in Cincinnati’s Hyde Park neighborhood for white people only. Church trustees at the time apparently accepted the gift with no discussion, he said.

“Part of your body tightens up the moment you read that language [of the will],” he said. “On further reflection, you are not at all surprised about it if you know the history of racism in this country.”

“As a present-day congregation, we continue to benefit from the wealth we were given in this gift,” he said. “That’s structural racism. That’s the piece we need to stop and lament. The accumulation of wealth is how structural racism works.”

Rather than villainize the donor or her donation, Knox’s leadership, led by the session, determined to tell the church’s story broadly and to confess it. “This is a story that allows us to talk about structural racism in a way that has relevance for us,” Fronczek said. “If you want to understand what [structural racism] looks like, this is a story about us.”

A pivotal sermon

In June, Fronczek delivered a straightforward and powerful sermon discussing the gift and the initial steps the session had taken to confess and lament that chapter of Knox history.

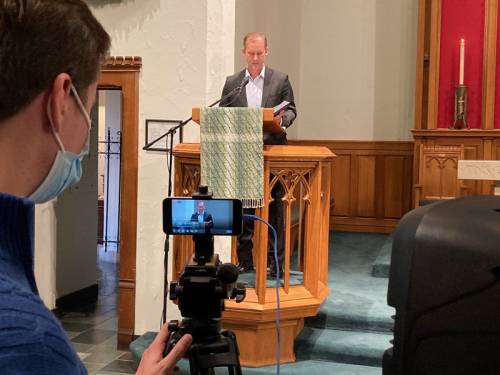

The Rev. Adam Fronczek preaches in a near-empty sanctuary as part of a livestream service in November. (Mike Fitzer/180 Degrees)

“It was hard, particularly for white people, to get used to talking about racism,” he said. “It’s fraught with the possibility that people aren’t ready for the conversation or don’t want to have it. We have taken many steps to say, ‘We don’t want to leave anybody behind on this. We want you in on the conversation wherever you are.’”

“There is so much harm done,” he added, “by people who want to look back at racism and say, ‘That’s not who we are anymore, and thanks be to God! If this were to happen again, we would react differently.’”

“Who knows if that’s true?” he said.

The session, he said, convened congregational listening groups, and then committed to a three-part racial justice ministry: Listen, Learn and Act. “We will keep listening to the community and externally to friends more diverse than our own,” Fronczek said of the initial stage. Learning involves a commitment to “keep doing the internal work.” Acting will include everything from making significant financial commitments to “offering opportunities to do and be the church in ways that break us out of the patterns and structures we continue to participate in,” Fronczek said.

Knox Presbyterian Church Ruling Elder Kerry Duke said his heart became convicted over structural racism during the 2019 NEXT Church national gathering in Seattle. (Mike Fitzer/180 Degrees)

Knox Ruling Elder Kerry Duke said attending the 2019 NEXT Church national gathering in Seattle as well as reading books including Michelle Alexander’s “The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness” helped him become aware that “head knowledge is not quite enough. There was a heart that needed to be worked on as well.”

Duke returned from that NEXT Church gathering determined to, as he said, “begin the conversation. I think our church is fairly attuned to what’s going in society.” However, “it’s difficult for old white guys like me to understand [structural racism]. And it’s been difficult during the pandemic, but I think we are wrestling with it.”

He defined structural racism as “systems all around us that we enjoy and take part in without recognizing some injustices are built into those systems. We don’t recognize those injustices because we move in circles that are isolated. We need to get beyond that and stand with the other to recognize those injustices more.”

For Duke, that recognition can be painful. His niece is married to a Black man who was formerly the night manager at a Louisville, Kentucky, fast food restaurant. One month, the man was pulled over 17 times by the same police officer. That unfair treatment brought tears to Duke’s eyes during a recent interview.

“It’s personal,” he said.

Championing justice

Heidi Knellinger, who describes herself as “a proud member of Knox Presbyterian Church” and is a current session member and youth leader, identifies as “a strong justice person overall.” She and her wife have been together for 38 years and have three children. “When you are a champion of justice, it goes across all boundaries,” Knellinger said.

Ruling Elder Heidi Knellinger sees her role as a “fixer,” especially for social justice issues. (Mike Fitzer/180 Degrees)

She remembers the day the session shared the bequest story with the rest of the congregation.

“I am an emotional person and a fixer,” Knellinger said. “I had an immediate visceral reaction to the news that our church had been part of such an action. My immediate reaction was to fix it, and I think a lot of people around the table had the same reaction.”

“A lot of people said, ‘That was 100 years ago. It’s clearly not who we are today.’ It was all along the spectrum,” she said of congregation’s reactions. “To me, education is the key to bringing people along, changing hearts and perspectives on things that are difficult.”

Church members read books and watched videos together “and did a lot of intellectual work,” she said. The church’s Racial Justice Task Force “dug a little deeper and did more relational work … I feel that is where our work is going — changing our hearts, which will change how we view the world — and then take action from there.”

“I now see injustice and racism everywhere,” Knellinger said. “It’s part of my fixer nature, and it makes me want to act.”

‘I’m not going to be mad at Knox right now’

Ruling Elder Maggie Gieseke said the news of the bequest “moved me to tears.” She and her husband are the parents of three birth daughters as well as two sons from Guatemala and a daughter from Ethiopia.

“Church is very much a part of their lives,” she said, speaking of their adoptive children. “To hear they were disqualified from all of that, it was upsetting. It made me angry.”

Ruling Elder Maggie Gieseke, the mother of two adoptive sons from Guatemala and a daughter from Ethiopia, says the church “benefitted from an anti-Christian act, and we need to do something to fix it. (Mike Fitzer/180 Degrees)

She spoke “right then and there” about her feelings to Fronczek, who “listened and was there for me. He offered some suggestions to work through it and talk to my children about it, so that in time we could move beyond it.”

Their 12-year-old daughter from Ethiopia was also upset. But she told her mother, “it was a long time ago. I’m not going to be mad at Knox right now.” The children from Guatemala expressed similar sentiments, Gieseke said.

“They’re not as mired down in what’s happened in the past,” she said. “I don’t know if it’s forgiveness. Maybe ‘hopeful’ is the right word.”

“We recognize everyone comes to this differently as part of their racial justice journey. As a task force, we’ve had to wrestle with that,” Gieseke said. “There is a time to listen, a time to learn and a time to act … We have benefitted from an anti-Christian act, and we need to do something to fix it. That involves sharing our story and listening to diverse voices.”

Hearing from diverse voices

Knox Presbyterian Church has long been involved in ministry with Third Presbyterian Church, a largely Black congregation served by Ruling Elder Rodney Christian, who’s also the president of the East Westwood Community Council. Christian’s passion is running a feeding and tutoring operation out of the basement of the church.

Rodney Christian of Third Presbyterian Church in Cincinnati runs a feeding and tutoring operation out of the basement of the church. (Mike Fitzer/180 Degrees)

“It was sad to learn [the bequest] was for that purpose, but I felt that the confidence I had with Knox Presbyterian Church overrides a lot,” Christian said while seated in the basement where so much ministry occurs. Third Presbyterian Church has also completed construction of an outdoor basketball court and playground to further its ministry.

“Our kids,” Christian said, “get impacted by our relationship with Knox.”

It’s important, he said, for people and congregations to find their voice to talk about working to end structural racism.

“We all have a platform or a stage — in our homes, on our jobs and in our communities,” he said. “You start performing togetherness and love on the stage you’re on right now, then build from that. It has to be a movement, not a moment.”

“It’s a huge step Knox is taking,” he said. “We have to let people see us do this together, to talk in public outside these walls so people can see us. We are all stars in our own little circle,” he said with a smile. “We have to perform in a way that God smiles down on us.”

To Christian, the most rewarding partnership between Knox and Third churches has been tutoring.

“Kids gain relationships with someone who looks totally different from them. That’s huge for me, because I am big on race relations,” Christian said. “We now have a community garden, something we never had before. It’s saying we do matter.”

As president of the community council, “I like us to be able to do things on our own. But we need help; there’s no doubt about it,” Christian said. “Just get us started and let us go for it, because I think that’s good for the community. A dream is to have more Black-owned businesses. A lot of people have proven themselves that they can do that.”

“I just like going out and doing the work,” he says of his personal motivation. “God is up to something.”

“You have done a wonderful prophetic job,” Fronczek told him, “reminding us to keep showing up.”

Developing some muscles

Still, Fronczek said, he and others at Knox “wonder how many times we have thrown our weight around” even while working with Third Presbyterian Church “and done things that are hurtful. I hope and pray we will grow more and more comfortable naming when the hurt happens … while we work on the partnership with the community at Third, who knows what they need.”

Knox has also started conversations with other churches in Cincinnati Presbytery. “We are thinking how that might be a response to the General Assembly asking congregations and presbyteries to have conversations,” including disparities in ability to pay for pastoral leadership, Fronczek said. “We haven’t arrived. We’re just getting started.”

Knox has committed to the Matthew 25 invitation. “In our history we can point to lots of what Knox has done because we profess to care for racial justice,” Fronczek said. “But when we look at injustice in our city, there were times we may have talked about it, but we weren’t necessarily showing up.”

The congregation has voted to budget $50,000 each year to support the work of racial justice. In 2020, Knox’s total budget is about $1.7 million.

“There is a lot more work ahead of us than behind us,” Fronczek said. “We are a 98% white congregation that participates in a lot of harmful systems and structures, and I am a white pastor who says and does things that are hurtful.”

“We’ve got to develop some muscles, some energy and some ability to make mistakes along the way,” he said. “How that will shape out in the future I don’t know, but it does feel like a vital conversation.”

![]() You may freely reuse and distribute this article in its entirety for non-commercial purposes in any medium. Please include author attribution, photography credits, and a link to the original article. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDeratives 4.0 International License.

You may freely reuse and distribute this article in its entirety for non-commercial purposes in any medium. Please include author attribution, photography credits, and a link to the original article. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDeratives 4.0 International License.

Categories: Matthew 25, Racial Justice

Tags: bequest, ethiopia, guatemala, heidi knellinger, hyde park neighborhood, kerry duke, knox presbyterian church cincinnati, maggie gieseke, matthew 25 invitation, michelle alexander, NEXT Church gathering, rev. adam fronczek, rodney christian, structural racism, the new jim crow: mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness, third presbyterian church cincinnati

Ministries: Matthew 25 in the PC(USA): Join the Movement, Gender, Racial and Intercultural Justice