Worship is steeped in history, rich in hope

By Donna Frischknecht Jackson | Presbyterians Today

First Presbyterian Church in Springfield, Ill., has traditionally held an 1850s carol sing, complete with period clothing and an appearance from Abraham Lincoln. This year, it will host a Watch Night service. Courtesy of First Presbyterian Church

Anna Shvets/Pexels

The sanctuary lights of Shiloh Presbyterian Church in Oxford, Pennsylvania, begin dimming. The small gathering who ventured into the nippy December night make their way from their pews to encircle the perimeters of the room. Their steps are slow — prayerful. Before COVID-19, hands wouldn’t hesitate to reach out to another, seeking to be clasped, strengthening the fellowship among those in the room. When the circle completes, prayers thanking God for the blessings of the year that is ending begin. “Gracious God, I thank you for …” “Redeemer and Sustainer, I praise you for …”

What comes next is John Peter Wolf Jr.’s favorite part of this worship service known as “Watch Night.” A lit candle is passed to each person in the circle. “We then share what we hope the new year will bring,” he said.

Wolf, who serves as Shiloh Presbyterian’s clerk of session and organist, grew up in the church, and remembers many a Watch Night. And while the attendance of the Dec. 31 service has dwindled over the years — pre-COVID-19 there were about 35 people in the sanctuary, he says — the healing one can experience on such a night has not diminished.

“Those prayers are a way to put into perspective all that has transpired over the past year,” said Wolf. More importantly, he adds, it is an opportunity to step into the new year with “burdens dropped” and with “renewed hope.”

This tradition of embracing the hope of a brighter tomorrow is not unique to just Shiloh Presbyterian Church, which was organized in 1874 with just nine members after the wives of faculty at Lincoln University petitioned the Presbytery of Donegal to establish an African American congregation. Shiloh joins other African American congregations from varying denominations around the country in gathering to “watch during the night” just as their enslaved ancestors once did on the eve of promised freedom.

Liberty to dawn

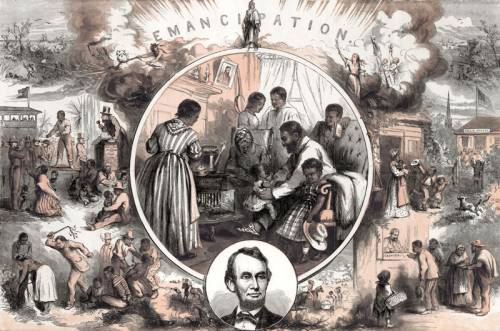

Dec. 31, 1862. The air was electric with anticipation. The long-awaited freedom yearned for was seemingly within reach for the enslaved African Americans who gathered that night, many in secret. A few months earlier on Sept. 22, President Abraham Lincoln had issued an executive order known as the “Emancipation Proclamation.” The proclamation, which would free the enslaved, would not take effect until the stroke of midnight. And so, on the last day of 1862, the enslaved gathered to watch for the calendar page to turn and, with it, their lives to change.

Frederick Douglass, an abolitionist, writer and statesman, captured the feeling of hope reverberating in the crowded small cabins where many met. “It is a day for poetry and song, a new song. These cloudless skies and this brilliant sunshine are in harmony with the glorious morning of liberty about to dawn up on us,” he wrote.

While that “morning of liberty” would not shine as brilliantly as originally hoped — the work of racial equity continues today — a new American tradition was born. Up until then, there had been variations of Watch Night services. An early reference to a Watch Night service appears in 1733 when a group of Moravians held a service of “watching and waiting” at the palace of Count Nicholas von Zinzendorf in Herrnhut, Germany. John Wesley, founder of the Methodist Church, brought a version of the service to America in the late 18th century. Among the enslaved, though, they and future generations would continue meeting on Dec. 31 for Watch Night or, as it is sometimes called, “Freedom’s Eve.” For them, it would become a night to lift prayers, sing songs and hear once again the reading of the Emancipation Proclamation.

By doing so, a tradition steeped in history is not only being kept alive among African American congregations, but a growing number of white congregations are discovering — and learning from — Watch Night services. Among them is First Presbyterian Church in Springfield, Illinois, which will be hosting its first Watch Night this year.

Welcoming a new tradition

The Rev. Susan Phillips, who came to First Presbyterian Church, Springfield, in 2017, is no stranger to getting conversations on racial justice started that can pave the way for a more inclusive community. During her 18 years serving First Presbyterian Church in Shawano, Wisconsin, Phillips was instrumental in creating a Martin Luther King Jr. Day program.

So, when Springfield’s Abraham Lincoln Association, which was founded in 1908 to promote Lincoln’s life and legacy, contacted her to host a Watch Night event, Phillips didn’t hesitate with a resounding “yes.”

“I’ve been working on dismantling systemic racism here in the community for the past three years. I knew about Watch Night traditions from having lived in Georgia. I knew of how the enslaved would gather in whatever spaces were safe to watch and wait for freedom,” she said.

Having First Presbyterian host Watch Night made perfect sense as the church has connections to the president who had issued the Emancipation Proclamation in 1862. Known as “the Lincoln church,” First Presbyterian was the place where the first family had rented a pew. It was Mary Todd Lincoln, though, who often graced the church doors, not Abe, Phillips says.

Famous parishioner aside, the hosting of a Watch Night service continues the longstanding tradition of First Presbyterian being a witness to racial justice in the community. The year the Abraham Lincoln Association was organized was also a trying time in Springfield’s history. What was to become known as the 1908 Race Riot saw Springfield’s Black community destroyed with houses and businesses burned. Two Black men were lynched, adds Phillips. It was said of the then-pastor of First Presbyterian, the Rev. Thomas D. Logan, that he “put courage into the whole city in its weakest and lowest hour.”

The Watch Night service will be a departure from the holiday tradition that Phillips’ congregation has embraced for years — an 1850s carol sing in honor of Mary Todd Lincoln’s birthday on Dec. 13, 1818. The carolers dress in period clothing. Abraham Lincoln even makes an appearance, says Phillips.

When Phillips first arrived at First Presbyterian, she wondered if the carol sing was “a show or a worship service.” She soon discovered it was more faith-filled — and truthful — of that period.

“While there weren’t explicit references to slavery, there were echoes of the struggle the country was facing in the songs and the prayers,” said Phillips.

For example, the English translation of the Christmas hymn “O Holy Night,” which is part of the carol sing, is actually rooted in the abolitionist movement. The original French text was written by the poet Placide Cappeau in 1843 and set to music by Adolphe Adam in 1847. In 1855, John Sullivan Dwight, a Unitarian minister from Boston, while translating the French text, noticed the lines in the third verse embraced his abolitionist viewpoint. He then translated that verse to read: “The Earth is free, and Heaven is open. He sees a brother where there was only a slave; love unites those that iron had chained.” Today, that line of the verse is sung: “Chains shall he break, for the slave is his brother.”

Last year, with the pandemic still raging, First Presbyterian did not hold its 1850s carol sing. “There is just something about the feel of the sanctuary bathed in candlelight that couldn’t be replicated through Zoom,” said Phillips. But that didn’t stop the conversations that the carol sing initiated: What were the dynamics taking place during the 1850s?

“This led us to doing a special production for Black History Month,” said Phillips, where historic figures such as Abraham Lincoln and Harriet Tubman dialoged with one another. Watch Night will continue these conversations.

“We have this rich history that we treasure, and not just the Lincoln connection,” said Phillips. “We have this history of having the conversation of faith and race.”

The evening, planned by members of the Abraham Lincoln Association, will include prayers, snippets of historic readings and inspirational songs. The highlight for Phillips, though, will be the reading of the 719-word Emancipation Proclamation.

Back at Shiloh Presbyterian Church in Pennsylvania, Wolf says that he is looking forward to being back in person for its Watch Night tradition. The organist is looking forward to playing songs such as “We’ll Understand It Better By and By” and “Another Year is Dawning.” He looks forward to holding that candle and sharing his hopes.

“Watch Night is a testimony to a moment from the past that can shape the future,” said Wolf. “Folks need to hear its message of freedom still to come.” And perhaps, the faithful at Shiloh, a name it adopted in 2015, which means “peace,” will be watching the night for just that: peace in the world.

Donna Frischknecht Jackson is editor of Presbyterians Today.

A Watch Night tradition

Reading the Emancipation Proclamation

The reading of President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation is often part of the Watch Night service in many congregations. Here is an excerpt from the proclamation:

The reading of President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation is often part of the Watch Night service in many congregations. Here is an excerpt from the proclamation:

That on the first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free; and the Executive Government of the United States, including the military and naval authority thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons, and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom.

That the Executive will, on the first day of January aforesaid, by proclamation, designate the States and parts of States, if any, in which the people thereof, respectively, shall then be in rebellion against the United States; and the fact that any State, or the people thereof, shall on that day be, in good faith, represented in the Congress of the United States by members chosen thereto at elections wherein a majority of the qualified voters of such State shall have participated, shall, in the absence of strong countervailing testimony, be deemed conclusive evidence that such State, and the people thereof, are not then in rebellion against the United States.

Support Presbyterian Today’s publishing ministry. Click to give

![]() You may freely reuse and distribute this article in its entirety for non-commercial purposes in any medium. Please include author attribution, photography credits, and a link to the original article. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDeratives 4.0 International License.

You may freely reuse and distribute this article in its entirety for non-commercial purposes in any medium. Please include author attribution, photography credits, and a link to the original article. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDeratives 4.0 International License.