As numbers dwindle, relationships grow

By Sue Washburn | Presbyterians Today

José L. Muñoz is one of the growing number of CREs — commissioned ruling elders — who find themselves shepherding small congregations like First Presbyterian Church of New Braunfels, Texas. Courtesy of First Presbyterian Church of New Braunfels

When the God of the Universe decided to make a change in human history, it didn’t happen as a big, cosmic event, but rather as the birth of an infant. As we celebrate the coming of Jesus for our salvation, we remember that he was born to an ordinary family in the small town of Bethlehem.

Christmas is a good time to remember that God’s presence and power can call forth big changes in even the smallest churches that follow in Jesus’ footsteps. Those changes are not necessarily in numerical growth, but in the personal impact they have on the lives of the people around them. A big transformation can start small: a simple worship service, a ride home from work or a meal delivered after the birth of a baby.

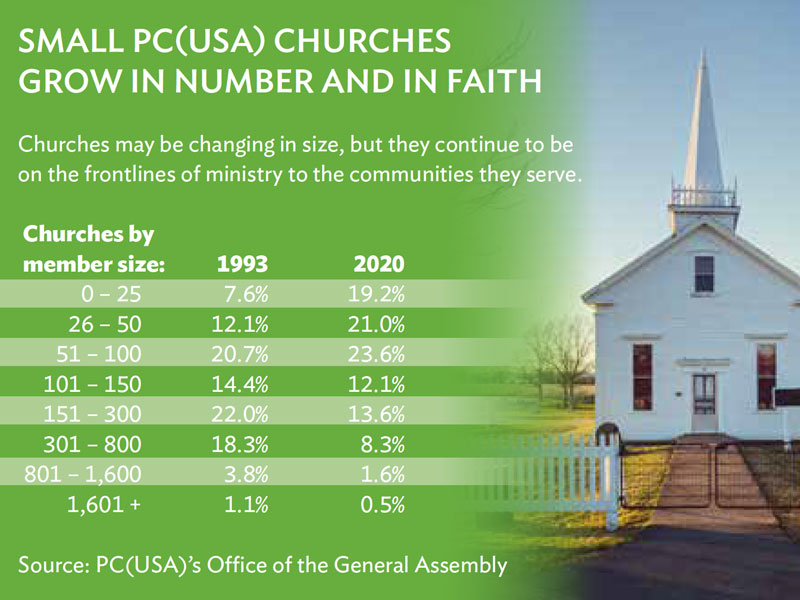

Churches are changing in the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.), and what ministry looks like is changing with it. Congregations are getting smaller, and ministry is getting more personal. According to the Office of the General Assembly, in 2020, more than half (63%) of the churches in the denomination had fewer than 100 members and 40% of PC(USA) members attended a church with fewer than 50 members.

As the Jesus story shows, small doesn’t mean weak or ineffective. Take for instance the fact that the median size of a church in the Presbytery of West Virginia is 26 members. Many of the churches can’t afford a full-time pastor, and yet they continue to spread the gospel, care for each other and work for justice.

“Despite their size, even our smallest churches continue to bring value to the communities they are in, even without sustained pastoral leadership,” said the Rev. Dr. Ed Thompson, general presbyter of the Presbytery of West Virginia. “Any size congregation can be faithful. You don’t have to have 2,000 or 200 members. Even 20 people can witness to the gospel and care for the community. Small churches are on the front lines in our towns and rural communities.”

The gifts of small churches often go unnoticed amid the novelty of online worship and other technical innovations. But small churches have been reaching their communities during the pandemic with communion by phone, as well as cards and notes, and even printed worship liturgies and Sunday school lessons that get stamped and mailed.

The gift of partnerships

With a total membership of 65 and 20 to 30 in worship each Sunday, First Presbyterian Church of New Braunfels, Texas, proclaims itself as “a little church with a big heart.” When COVID-19 prevented large gatherings at Thanksgiving last year, the congregation wanted to reach out to the people in their community.

“We wanted to do something, but we didn’t know what it was,” said José L. Muñoz, who is a commissioned ruling elder (CRE). CREs are trained in certain pastoral duties without having obtained a Masters of Divinity degree. “We ended up doing a Thanksgiving lunch ‘to go’ and passed plates of food to 350 people. It allowed us to connect.”

First Presbyterian has a new building and is seeing growth in the surrounding community. While they would like to see the church grow, they don’t feel the need to wait for more members to engage in the mission God has given them.

The church was organized in March 1931, becoming what was then the Iglesia Presbiteriana de New Braunfels. It had 18 charter members and 12 children.

“We don’t have a lot of money, but God has given what we need for our ministry. God empowers us, and we give God all of the glory and honor,” Muñoz said.

A small church, though, may find that it just doesn’t have the people to undertake some projects by itself like New Braunfels’ Thanksgiving meal.

As First Presbyterian Church of Duquesne, Pennsylvania, discovered, partnerships are the foundation for mission. The church serves one of the most under-resourced communities in Pennsylvania and has functioned with a part-time pastor for 29 years.

“Small churches often think they don’t have enough people or resources to reach the community,” explained the Rev. Dr. Judith Slater. “But when done in partnership with other churches or community organizations, it really only takes a handful of folks from a congregation to organize ways to engage.”

Slater points to the community garden that is on the church property. More than 30 gardeners from the area help maintain it, but only a handful are members of the church. “The team approach is an exciting model for small churches,” Slater said.

The gift of deep-rootedness

With 21 members, Ketchikan Presbyterian Church in Ketchikan, Alaska, hasn’t let its small size thwart the work of serving others in the community. Courtesy of Ketchikan Presbyterian Church

With 21 members, Ketchikan Presbyterian Church in Ketchikan, Alaska, does not expect much numerical growth in the surrounding community or even in church membership. The town is bordered by the Pacific Ocean on one side and the Tongass National Forest on the other side, so there is literally no space for the picturesque, cruise ship town to expand.

“We are a little strip of civilization between the Pacific Ocean and the forest,” said elder Grace Kinney. “Our strengths are our dedication and our diligence.”

“We are not anticipating a lot of growth in our area,” added her husband, Stephen Kinney, also an elder of the church. “If the cruise ships recover from the COVID-19 pandemic, we might see some growth, but we are not expecting it here.”

The members of Ketchikan think beyond numbers when they ponder what it means to grow. They recognize that many people in the area have deep roots and hope to encourage others to grow in faith where they are.

When they can gather safely, Ketchikan serves an ecumenical dinner for about 60 people per month, and when the COVID-19 transmission levels spike, they adapt and make it a takeout meal.

“Our membership may be small, but it’s a good cross section of the community,” Kinney said. Ketchikan’s membership is about 50% white and 50% Native.

Ketchikan Presbyterian shares a part-time pastor with a local United Methodist church. They also count on lay leadership to help guide the church. Finding pastoral leadership for small congregations in remote places can be challenging. Ketchikan’s previous pastor had to commute by plane or boat. Such challenges have made the congregation better able to pivot with changing circumstances long before COVID-19. They’ve had to change worship times and styles with each new pastor.

The gift of lay leadership

First Presbyterian Church of Lenoir, North Carolina, went from several hundred members to a membership of around 30 when most of the congregation voted to leave the PC(USA) several years ago. The faithful remnant sought to create a fully inclusive church. The small group was able to keep the name and some of the financial resources, but not the building. Instead, they met in homes before eventually renting a space for worship.

Most members are over the age of 50, and many are active in the life and leadership of the church. The clerk of session is a master gardener and brings flowers to worship each week. A former pianist in her 90s brushed up her skills to play for worship services. The Rev. Beth Ann Miller serves the congregation part time and is inspired by the members.

“They’ve come together in a beautiful way,” she said. “They’ve managed to let go of the big church framework and recognize the resources they do have can be used for others.”

Miller added that being split from the bigger congregation allows First Presbyterian to be more focused and intentional about its mission of dismantling structural racism as a Matthew 25 congregation.

The gift of relationships

Miller pointed out that small churches are reflective of the first-century house churches that the apostles founded in the early days of the faith. Each Sunday feels like a family reunion, and in some small churches it is, since one or two families make up the majority of the congregation.

“The benefit of a small church is that you know who everyone is. You don’t feel like you are being marginalized or on the outside,” said Muñoz, of First Presbyterian, New Braunfels. “We call ourselves ‘the little church with a big heart.’ That’s what a small church can be to people.”

“The benefit of a small church is that you know who everyone is. You don’t feel like you are being marginalized or on the outside,” said Muñoz, of First Presbyterian, New Braunfels. “We call ourselves ‘the little church with a big heart.’ That’s what a small church can be to people.”

Slater, of First Presbyterian, Duquesne, looks at the faith and resilience of the church she serves and wonders why the church hasn’t grown. “I’ve been in Duquesne for 29 years. At times it’s been a mystery why the church hasn’t grown. But if we grew numerically, we might not be the same church relationally.”

For First Presbyterian, Duquesne, ministry sometimes looks like picking up a teenager from a late shift at a fast-food restaurant because the buses aren’t running or helping to raise funds so that a young woman can get a culinary arts degree.

The gift of flexibility

For churches that have recently seen their numbers drop, adjusting to ministry as a small church can be a challenge. Members mourn for the past and experience anxiety about the future. They also find that they may no longer have the energy to maintain programs that have worked in the past.

“We don’t have to continue a program until the end of time,” Slater said. “Small churches need the flexibility of responding to the current situation and letting go of what is no longer needed.”

Miller said that rather than have meals in their worship space, members often go to a restaurant after church, pulling together tables and eating as a community. This saves the members from the setup and cleanup and still allows them to enjoy each other’s company.

At Duquesne, rather than scale back the meal to a coffee hour, the members have chosen to continue to have lunch together in the building after worship.

“You have a deeper conversation over lunch than you do over a doughnut,” said Slater.

Resilient small churches are open to change and alternative forms of ministry, including a part-time or shared pastor with other churches or even other denominations, as Ketchikan demonstrates. Many small churches are using commissioned ruling elders to lead as well.

Thompson believes that small churches are the future of the faith. While large churches have their place, small churches will continue to serve God’s people in a new way, but they may have to change how they do it.

“Many small churches won’t get a full-time, seminary-trained pastor. Instead, our small churches will have to grow their own leaders. Churches need to identify their members with gifts for ministry and encourage them into church leadership, not just as an elder or deacon, but in the pulpit,” Thompson said.

As the number of small congregations increases, the gifts that they offer need not decrease. Slater points out that small communities of faith are what started the Jesus movement. “A small church is as close as we can get to the way Jesus and his disciples approached their ministry together.”

Sue Washburn is the transitional pastor at Union Presbyterian Church in Murrysville, Pennsylvania, and a freelance writer.

Support Presbyterian Today’s publishing ministry. Click to give

![]() You may freely reuse and distribute this article in its entirety for non-commercial purposes in any medium. Please include author attribution, photography credits, and a link to the original article. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDeratives 4.0 International License.

You may freely reuse and distribute this article in its entirety for non-commercial purposes in any medium. Please include author attribution, photography credits, and a link to the original article. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDeratives 4.0 International License.

Categories: Presbyterians Today

Tags: commissioned ruling elder, CRE, lay leadership, TAGS Small churches

Ministries: Presbyterians Today