Weary walkers on Appalachian Trail find a respite

By Sherry Blackman | Presbyterians Today

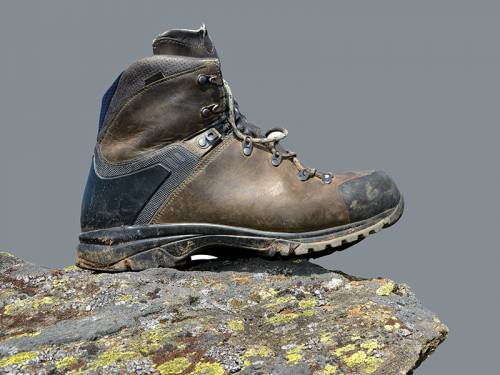

Ascend the church’s steep driveway on any given day during peak hiking season — March through November — and you’ll see pup tents pitched on the church’s grassy knoll. Flanking the driveway are plastic lawn chairs doubling as drying racks, draped with underwear, pants, shorts and soggy socks of every size and color, drying in the sun and wind. Backpacks are opened to breathe needed fresh air and an array of hiking boots, creased and worn from the sharp Pennsylvanian rocks, rest nearby, exhausted from the journey.

Ascend the church’s steep driveway on any given day during peak hiking season — March through November — and you’ll see pup tents pitched on the church’s grassy knoll. Flanking the driveway are plastic lawn chairs doubling as drying racks, draped with underwear, pants, shorts and soggy socks of every size and color, drying in the sun and wind. Backpacks are opened to breathe needed fresh air and an array of hiking boots, creased and worn from the sharp Pennsylvanian rocks, rest nearby, exhausted from the journey.

Inside the hostel, in the basement of the church, is a communal living room, typically strewn with gear and food. A bunk room that sleeps eight, as well as a shower room and a separate bathroom, is also in the church’s basement.

Hikers bring hope

The outreach to hikers literally transformed the Presbyterian Church of the Mountain. Larry Beck, a long-serving church elder, was involved at its inception, when stated-supply pastor William H. Cohea designed a presbytery-funded survey to assess the needs of Appalachian Trail hikers passing through Delaware Water Gap.

Beck recalls: “In 1976, the church was in trouble. It was dying. Only 15 congregants gathered for worship each Sunday, and did little else. The church did some soul-searching about how they could show God’s love in the world. After much discussion and prayer — and yes, some resistance and more prayer — we decided we would start on this journey by opening our church building to Appalachian Trail hikers, since the church is located right on the trail as it crosses from Pennsylvania into New Jersey.” Today the church has 130 members. Their hands-on ministry to hikers involves both the oldest and youngest congregants, who gather to serve and interact with dozens of hikers every Thursday evening of the summer for a potluck hot-dog dinner.

The Hiker’s Center at the Presbyterian Church of the Mountain welcomes hikers with a place to rest, shower, eat and enjoy fellowship with one another. Sherry Blackman

The ministry, however, goes beyond sharing food and table talk. Every day during peak season, in a scheduled rotation, a member/volunteer cleans and freshens the rather odoriferous Hiker’s Center. Others lug home shower room towels provided by the church, which they launder and return. Still others are on speed dial to transport injured or ill hikers to doctors or emergency rooms, or to nearby stores to purchase supplies. The Rev. Karen Nickels, who served the church for more than 25 years, says the congregation thrives because the members are focused on the needs of others, rather than on themselves.

“The church practices the spiritual discipline of hospitality — creating a space which is safe and free. It meets the needs of the other without asking for anything in return,” Nickels said. One example of this hospitality is David Childs, steward of the hiker mission for more than 20 years. He, along with the pastor, is always on call, attending to the needs and concerns of hikers. Many times, though, simply being there to listen is what hikers need the most, he says, adding, “Listening is an act of compassion.”

Childs checks in on those staying at the Hiker’s Center at least once a day, hearing their concerns and sharing his experiences as an Outward Bound instructor who climbed to the top of Denali, the tallest mountain in North America. He offers the hikers practical tips and emotional encouragement. By the time hikers have reached the Delaware Water Gap, nearly 1,300 miles from Georgia’s Springer Mountain, they’re well over halfway to Mount Katahdin.

“Hiking the trail is always one part spiritual pilgrimage,” Childs added.

Sacred stories

Members and friends of the Church of the Mountain believe in “being” rather than “preaching” when it comes to hospitality. For these folks, it’s all about listening carefully to the hikers who tell their stories about why they willingly, albeit reluctantly at times, have chosen to endure the hardships of the trail, and what the hikers are learning on their adventures.

Tents are a common sight on the lawn of the Presbyterian Church of the Mountain. Its hiker ministry has become a vital mission for the congregation. Sherry Blackman

Those at the church hear stories of old men grieving the loss of loved ones, of young people delaying the responsibilities of adulthood, of wounded warriors trying to “walk off” traumatic stress, and of those who are trying to heal from brokenness and addictions.

These welcomed travelers introduce themselves by sometimes puzzling trail names, like Sunshine, ISO, Psych and even Amazing Grace. The names are usually bestowed upon them by other hikers.

Several hikers attend Sunday morning worship during their one- or two-night stays. On one such Sunday last June, there were hikers from Austria, Germany, Australia, Scotland and the United States. For some, like Highlander, it was the first time they had ever attended church. Highlander, a midlife hiker from Scotland, said he was an atheist. But when he completed his hike, he rented a car to do some touring around the United States — and his trip included a stop at the Church of the Mountain to attend worship again. By extending hospitality to strangers, the church is showing God’s love in the world, and its passion for hospitality has grown, extending to other missions locally and globally. “God calls every church to missions of the Spirit’s choosing,” Nickels said. “The hikers ministry is one that Christ called this congregation to. It was right on their doorstep: Dirty, tired, sometimes ill, always hungry hikers were coming through town on the Appalachian Trail. Mission is about giving — and giving some more.”

Sherry Blackman is the pastor of the Presbyterian Church of the Mountain. She is also the author of Call to Witness, a story of one woman’s battle with disability, discrimination and a pharmaceutical powerhouse. She is working on her next book, Rev-It-Up: Tales from the Appalachian Trail.

Trail Tales

Walker, age 70

A soft-spoken, white-haired hiker, trail name Walker, was trekking the Appalachian Trail for the second time in three years. The first time he walked to grieve.

“I started in Tennessee in January. I was all alone and I screamed at God a lot. I cried my heart out, and I walked and I walked. By the time I reached Maine, I had physically and spiritually grieved my 4-year-old grandson who died from cancer the year before,” Walker said.

The second time he hit the trail, he was hiking as a chaplain, giving aid to whoever needed it along the way.

★

David Slaten, 40-something

David Slaten, trail name ISO — short for In Search Of —sported a long beard, a telltale sign of a thru-hiker, and had an almost POW-like physique, having dropped dozens of pounds during his venture, which is common among long-distance hikers.

He said he’d been craving hot dogs throughout his hike, and he was glad to have reached the Church of the Mountain just in time for the hikers’ feed.

“The phrase ‘free food’ is music to most any thru-hiker’s ears,” he quipped.

ISO revealed he was in search of the ability to forgive someone who had wounded him deeply, and he was in the process of deciding what he wanted to do next with his life. But he — like some other hikers, he said — had been wary of hunkering down in churches, out of fear of being bombarded with an evangelistic agenda.

“What I found at Church of the Mountain was different. I found a host of people who were happy to share their food and who had a general curiosity about my journey and the unique journey of all the hikers,” he said.

★

Joseph O’Donnell, 20-something

Joseph O’Donnell, trail name Psyche, found himself grieving anew the losses he had endured during his life. His younger brother Patrick had died of neuroblastoma, a rare pediatric cancer, when he was 3 and O’Donnell was5. On Christmas Eve 2003, when O’Donnell was 13, his father committed suicide. O’Donnell carried a photograph of his father and brothers with him on the trail. He recalled an especially profound experience on his Appalachian Trail pilgrimage.

“I had been hiking with a man whose trail name was Turtle, who was a minister from Virginia. We spoke about family, friendships and relationships, service to others, and faith in God. That he was a Christian minister and that I had chosen to hike the trail as part of my own discernment process seemed more than just a coincidence,” he said.

He encountered three other clergy on the trail — the Presbyterian pastor of the Church of the Mountain, a Baptist minister and a Catholic priest — who all independently encouraged him to pursue ministry. Last year, Psyche enrolled in seminary, with the intent to become a college chaplain.

Appalachian Trail statistics

The Appalachian Trail Conservancy reports that the number of hikers attempting a northbound (Georgia to Maine) “thru-hike” has more than doubled, from 1,460 hikers in 2010 to 3,735 in 2017. For hikers attempting a southbound thru-hike (Maine to Georgia), the number has nearly doubled, from 256 in 2010 to 489 in 2017. Hiking the whole trail usually takes about six months.

Eco-justice on the trail

An effort is underway by the Appalachian Trail Conservancy to educate hikers to “Leave No Trace” to preserve the trail, prevent environmental disasters and minimize the environmental and wildlife impact of the hikers. As part of this movement, every year a seasonal “ridge runner” is hired who cares for a stretch

of the trail. The responsibilities include dismantling active campsites in restricted areas, moving fallen trees and picking up garbage left behind.

![]() You may freely reuse and distribute this article in its entirety for non-commercial purposes in any medium. Please include author attribution, photography credits, and a link to the original article. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDeratives 4.0 International License.

You may freely reuse and distribute this article in its entirety for non-commercial purposes in any medium. Please include author attribution, photography credits, and a link to the original article. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDeratives 4.0 International License.

Categories: Presbyterians Today

Tags: hike, hiker, hikers, hiking, hospitality

Ministries: Presbyterians Today