By Rick Jones | Presbyterian News Service

The late 1960s marked the height of the civil rights era in the United States. Activists were stunned by the recent assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., and the nation was grappling with change.

As poverty and oppression continued their chokehold on communities of color, several activists, including James Forman, turned to mainline denominations to “step up” and make a difference. The Presbyterian Church took Forman’s message seriously—creating what came to be known as the Presbyterian Committee on the Self-Development of People.

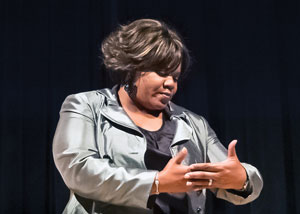

“It had to be a new form of ministry, not just charity,” says Cynthia White, SDOP coordinator. “It had to be a ministry of respect. They may need technical and financial assistance that the church can provide, but the community would own and control the projects.”

If people were facing economic challenges, this new ministry was prepared to help.

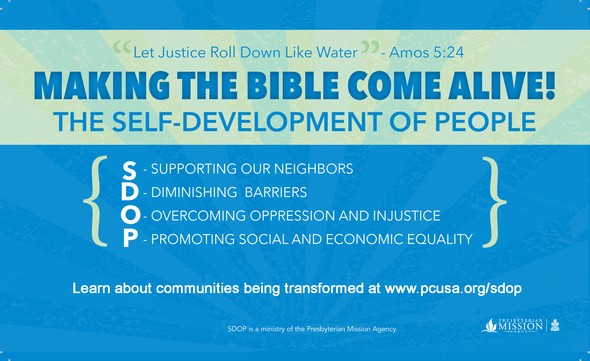

SDOP, 45 years later, has awarded more than $100 million to communities of economically poor, oppressed, and disadvantaged people in 67 countries. Nearly 5,600 projects have been designed to help communities become self-sustainable.

“It’s been a pleasure to work with some of the most committed and dedicated people in the church,” says White. “Keeping social justice on the front burner within the PC(USA) has been our main objective.”

White has been with SDOP since 1979 and has served as program coordinator for 13 years. She works with staff and a national committee, as well as 25 presbytery and three synod committees, to identify and work with communities struggling to meet the needs of their residents.

“One group, the Arctic Slope Native Association, in ’72 returned funds granted after winning their land rights case in ’74. The sons and daughters of the founders now run the association,” White says.

SDOP committee members, community partners, and colleagues all agree that its method has worked well.

“The dominant paradigm has promoted the idea that professionals and government leaders know best how to create change for people,” says Lisa Leverette, national committee member. “SDOP, through its experience and commitment to communities, has been a steadfast supporter of the unique focus on the underserved as the ‘expert’ to change conditions.”

In the United States, no major city has faced more economic challenges in recent years than Detroit. Its once robust economy and workforce continue to dwindle, forcing thousands out of work—who now struggle for daily needs, such as access to water. In 2013 the city filed for Chapter 9 bankruptcy, the largest municipal bankruptcy filing in US history, with a debt estimated at $18–$20 billion.

We the People of Detroit is a grassroots organization founded initially to fight against the mayor’s takeover of Detroit Public Schools in 2008–09. As thousands of people have struggled to provide for their families, the organization has taken on voting and workers’ rights, city assets, pensions, and self-governance and now works with households to prevent water shutoffs. SDOP worked with the organization to make some changes.

“Our partnership couldn’t have come at a better time,” says Monica Lewis-Patrick, cofounder and director of outreach for We the People. “It catapulted us into action. We had been working in homes and cars. SDOP helped get office space that was essential for training [and] meetings and provided us with a central location to store products.”

Internationally, SDOP has had the opportunity to work with cooperatives, agricultural groups, and other organizations.

“One of the most touching things I heard was in the Dominican Republic, when one of the leaders said to me, ‘Wow, you came back,’ ” White says. “We make it clear [that] SDOP is not a funder. Our work is about engaging with people as they struggle for social and economic justice.”

CREAS is an ecumenical fund created in Argentina to strengthen the capacity of the church and grassroots organizations in Latin America. Its purpose is to promote human dignity, justice, and peace. Since 2001, SDOP has contributed more than $290,000 through CREAS to assist oppressed and disadvantaged communities. Violence, high unemployment, and a weak education system have impacted thousands living in the region.

“The partnership between CREAS and SDOP has been one of mutual growth and common learning,” says Humberto Shikiya, CREAS’s founding director. “What I value the most from our partnership is trust, transparency, and fellowship. The most important value is the empowerment of oppressed people, and our inspiration is the love of God.”

White says communities aren’t the only ones blessed by their association with SDOP.

“A volunteer joined our national committee, saying he did not agree with the philosophy of financially supporting non-Presbyterian organizations,” she says. “However, when he left the committee six years later, he cried as he told us how much his life had changed through his association with SDOP.”

White believes a transformation takes place for those who are willing to roll up their sleeves and go to work.

Learn more and

take action

For more about Self-Development of People: pcusa.org/sdop

There are many ways to get involved with SDOP. Give to One Great Hour of Sharing, contact SDOP about serving on the national or a local committee, help plan a community workshop about SDOP’s grant application process, or invite SDOP-funded project speakers to your church.

“It transforms individuals and churches when [they assist] a community around the corner that is dealing with deplorable housing, residents who can’t afford to heat their homes, or a community infrastructure that lacks the resources to help their own citizens,” White says.

Other volunteers echo White’s statement.

“We live in our own little world and don’t realize how people have to sacrifice just to eat or get clean water,” says Cecilia Moran, who served as chair of an international task force.

Pastor Curtis A. Kearns Jr. served on the national committee in the 1980s, including a stint as chair. “I feel it is one of the most creative and important mission programs that the church is involved in, because our society is very competitive and aggressive,” he says. “Seldom are there programs which confirm and encourage people. SDOP is one program that does.”

Rick Jones is a mission communications strategist for the Presbyterian Mission Agency.

These poems . . .

from College and Community Fellowship’s Theater for Social Change, are adapted from the script The Letters Behind My Name. Funded by SDOP, the Theater for Social Change (collegeandcommunity.org) is a performance ensemble based in Harlem that uses theater to raise awareness about the impact of mass incarceration on women, families, and communities. Original performances are based on ensemble members’ life stories.

Three names

By Selina Fulford

I’ve had three names.

—“Yo, S!”

“S” was my street name, my mean-streets-of-Harlem name.

They called me “S” because we were in fast-mode,

the whole hustle and bustle of

using-selling-ducking-from-the-police mode.

No one had time to say “Saah leee naah,” no way.

It was “Yo, S!” There wasn’t time for a whole name.

—“Yo, S! On the count!”

My second name was a little longer,

but you still had to say it fast.

—“Male officer on the unit!”

98G–0032. You never forget that number.

In 1998, I was the 32nd woman to hit state ground.

—“Excuse me. I’m looking for Professor Fulford?”

Now that’s music to my ears.

Working during the day, going to school at night,

led me to an adjunct professor post.

“I’m Professor Selina Fulford. What’s your name?”

Dreams

By Vivian Nixon

Have you ever noticed a houseplant that has been placed in a corner in a dark room? Have you noticed that if there is even the tiniest window in the room, that plant, tucked away in a dark corner, will lean with all its might toward the sun? Everything that has life will struggle to survive.

Langston Hughes once asked what happens to a dream deferred. “Does it dry up / like a raisin in the sun / or fester like a sore / and then run?” Does it sag like a heavy load? Or does it explode?

I had a dream once. I dreamed that I’d be a great actress, able to move audiences to laughter or to tears. I aced my theater course that first semester at Oswego State. I was so happy when my grades came in the mail. I watched my mom open the envelope—I could hardly wait to hear her praise.

“Ha! I bet you were waiting for me to say, ‘Congratulations!’ Are you kidding me? You’re too ugly to be an actress. Change your major or I won’t pay another dime for tuition.”

On that day I took my dreams and began the slow and painful retreat to the corner of a dark room. I could feel my soul, and my dreams, gasping for breath every step along the way.

Almost suddenly, 16 years later, I looked up and saw a tiny window. With all my might, I leaned toward the sun. I felt my dreams leaning with me. Dreams have a life of their own.

These poems . . .

are excerpts of the original play Behind Closed Doors and were written by survivors of domestic violence who are part of the SDOP-funded organization Sisters Overcoming Abusive Relationships (soarinri.org). SOAR is a grassroots task force of survivors dedicated to changing systems that oppress women while educating the community about domestic violence.

Silent night

Warning: this poem could trigger domestic-violence victims

By Jenn Krafp

(sung) Silent night holy night all is calm all is bright

Alone

I stare at twinkling lights

Presents neatly wrapped

Stockings hung

Cookies and milk await Santa

Children sleeping

A rare moment of silence

Car pulls in driveway

Stumbling in door, slams

Yelling my name

“You’ll wake the kids”

“SHUT THE F*** UP YOU DUMB B****!”

Cowering, “Baby I’m sorry I don’t want to upset you it’s Christmas Eve and I just got them to sleep”

Tree crashing

Lights shattering

Face cracking

Silence shattered

Presents flying

Children crying

Daddy’s home.

“See what you made me do, b****? Calm them down and fix this s***. I’m going to bed.”

Door slams

Children sobbing

Head throbbing

Heart shattered

Dreams scattered

I’ve got to make this right

Sleep babies, Santa will come and make it better

“Mommy, will Santa bring us a nice daddy?”

Tears fill my eyes as I sing them to sleep

Fix the tree

Restring lights

Sweep broken glass

Mommy fixes everything

In the morning everything will be OK

Silent fight lonely fight everything will be alright

Don’t tell anyone our secret.

The s**t ignorant people say to DV survivors

By JS. K. Jallah

Are you okay?

Who was your abuser?

Why did you stay with him?

Why did you even choose a guy like that for a boyfriend?

You don’t look like the type of woman that would allow that in your life.

Why didn’t you tell your family?

Do you still love him?

Do I know your abuser?

No way, he doesn’t have an abusive bone in his body, he couldn’t hurt a fly.

You could have any man you want, why stay with an abuser?

You must like getting beat up.

What did you do to make him abuse you?

Why didn’t you press charges?

You should have gotten your brothers to beat his a**.

Were you that desperate for a man that you have to be with an abuser?

Are you sure you were abused?

Who was your abuser?

Why did you stay with him?

Why did you even choose a guy like that for a boyfriend?

You don’t look like the type of woman that would allow that in your life.

Why didn’t you tell your family?

Do you still love him?

Do I know your abuser?

No way, he doesn’t have an abusive bone in his body, he couldn’t hurt a fly.

You could have any man you want, why stay with an abuser?

You must like getting beat up.

What did you do to make him abuse you?

Why didn’t you press charges?

You should have gotten your brothers to beat his a**.

Were you that desperate for a man that you have to be with an abuser?

Are you sure you were abused?

Originally published in Presbyterian Today. Click here

![]() You may freely reuse and distribute this article in its entirety for non-commercial purposes in any medium. Please include author attribution, photography credits, and a link to the original article. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDeratives 4.0 International License.

You may freely reuse and distribute this article in its entirety for non-commercial purposes in any medium. Please include author attribution, photography credits, and a link to the original article. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDeratives 4.0 International License.

Categories: Peace & Justice

Tags: people power, SDOP, self development of people

Ministries: Presbyterian Committee on the Self-Development of People