Thousands cheer motorcade, gather at stadium for funeral

by Gregg Brekke | Presbyterian News Service

– additional reporting by Emily Enders Odom

Over 16,000 attendees filled the KFC Yum! Center in Louisville, Kentucky for an interfaith memorial service honoring the late Muhammad Ali. (Photo by Gregg Brekke)

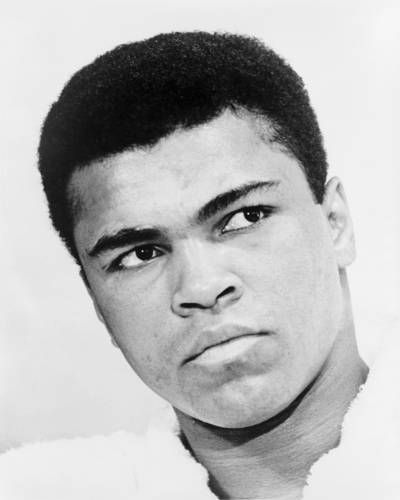

LOUISVILLE – The streets of Louisville, Kentucky were filled with thousands of people honoring Muhammad Ali this morning as his funeral procession traversed 19 miles through the city. Enthusiastic crowds cheered, threw flowers on the road and hearse, and chanted “Ali” as the 17-car motorcade passed Ali’s childhood home, the museum named after him, the boxing gym where he began his career, and the Presbyterian Center in downtown Louisville next to the KFC Yum! Center where an interfaith memorial service was held this afternoon.

An Islamic shroud covered the cherry-red casket that carried Ali, 74, to the historic Cave Hill Cemetery in Louisville for private burial prior to the memorial service. A traditional Islamic prayer service for the deceased, a Jenazah, was held last night at Louisville’s Freedom Hall.

Eulogists at the service included former President Bill Clinton, Billy Crystal, Bryant Gumbel, and Ali’s wife, Lonnie. Republican Sen. Orrin Hatch and national faith leaders also spoke at the public event attended by over 16,000 people.

A view from inside the Muhammad Ali interfaith memorial service at the KFC Yum! Center in Louisville, Kentucky. (Photo by Kathy Francis)

Lonnie Ali thanked the people of Louisville for their welcome and efforts to host a fitting memorial saying, “Muhammad never stopped loving Louisville.” She called upon his story of a stolen bicycle as a youngster and his encounter with a white police officer who encouraged Muhammad Ali to take up boxing. She said, “America must never forget that when a cop and an inner city kid talk to each other, miracles can happen.”

Saying Muhammad Ali’s religious convictions “caused him to turn away from war and violence,” she urged attendees to hear again his words, “It is far more difficult to sacrifice oneself in the name of peace than to take up arms in the pursuit of violence.”

Crystal joked about the length of the memorial service, then reminisced about his first meeting with Ali—a dinner where Crystal, early in his career, performed a skit impersonating sportscaster Howard Cosell’s dialog with the boxer. Following the routine Ali hugged Crystal, thanked him for making him laugh, and “to this Jewish white kid from Long Island imitating the greatest of all time,” Cyrstal said Ali whispered in his ear, “You’re my little brother. From now on I’m calling you my little brother.”

“Ali forced us to take a look at ourselves,” said Crystal. “This brash young man thrilled us, angered us, confused us, challenged us, ultimately became a silent messenger of peace and taught us that life is best when you build bridges between people and not walls.”

Praising Ali’s strength throughout his life, especially as he waged a 30-year battle with Parkinson’s disease, former President Clinton said, “In the end, besides being a tremendously fun man to be around, I will always think of him as a truly free man of faith… Being a man of faith, he realized he was never in full control of his life. Being free, he still knew he was open to choices. It is the choices that have brought us all here today.”

Tony De La Rosa, interim executive director of the Presbyterian Mission Agency, attended the service and said, “Muhammad Ali was a man of many gifts, who shared them graciously with the whole world because he was so grounded in his faith. He was a shining example of what God calls us all to be as a people of faith.”

Ali was born in Louisville on Jan. 17, 1942, as Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr., a name shared with a 19th-century abolitionist. His father, a billboard painter, was a Methodist but allowed Clay’s mother, who worked as a domestic, to raise their children as Baptists.

Ali was born in Louisville on Jan. 17, 1942, as Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr., a name shared with a 19th-century abolitionist. His father, a billboard painter, was a Methodist but allowed Clay’s mother, who worked as a domestic, to raise their children as Baptists.

Young Cassius Clay was introduced to boxing when he was 12 and boxed at the now closed Presbyterian Community Center in Louisville’s Smoketown neighborhood. The teen was extraordinarily gifted and amassed numerous amateur titles in youth boxing, culminating with a gold medal in the light heavyweight category in the Rome Summer Olympics in 1960.

In the early 1960s, Ali met Malcolm X, who was key in introducing Clay to the Nation of Islam, a group that was founded in Detroit in the 1930s as an amalgam of Islamic teachings and messianic claims. The World Boxing Association barred Ali after his conversion to Islam. Three years later, when Ali was drafted to fight in the Vietnam War he cited his beliefs as the basis for his refusal to serve, and that would lead to a total exile from the sport.

“My conscience won’t let me go shoot my brother, or some darker people, or some poor hungry people in the mud for big powerful America,” as he put it. “And shoot them for what? They never called me nigger, they never lynched me, they didn’t put no dogs on me, they didn’t rob me of my nationality, rape or kill my mother and father. … How can I shoot them poor people? Just take me to jail.”

Ali was convicted of draft evasion in June 1967 and sentenced to five years in prison. He remained out on bond while he appealed, but he was barred from all boxing, from the age of 25 to almost 29—his prime.

He was able to begin boxing again in 1970, and a year later, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned his draft evasion conviction in a unanimous ruling. Famous for his self confident and humorous banter with reporters, Ali professed himself “the greatest” and “king of the world” when questioned about his fighting prowess, drawing the ire of his opponents while garnering worldwide respect.

As Ali reestablished his reputation as a brilliant and fearsome fighter, he also continued to speak out against racism, war and religious intolerance. All the while, he projected an unshakeable confidence and humor that became a model for African-Americans.

“Ali advanced something that Presbyterians seek to do: to break down the barriers between people of different faiths to work together for peace and justice,” said t he Rev. Dr. Charles Wiley III, coordinator for the Presbyterian Mission Agency’s office of Theology and Worship.

Quoting the “The Interreligious Stance of the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.),” a policy statement adopted by 221st General Assembly (2014), Wiley added, “Presbyterians see these interreligious relationships ‘as a specific instance of Christ’s universal command to ‘… love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind’ and to ‘love your neighbor as yourself’ (Mt. 22:37, 39).”

![]() You may freely reuse and distribute this article in its entirety for non-commercial purposes in any medium. Please include author attribution, photography credits, and a link to the original article. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDeratives 4.0 International License.

You may freely reuse and distribute this article in its entirety for non-commercial purposes in any medium. Please include author attribution, photography credits, and a link to the original article. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDeratives 4.0 International License.

Categories: Ecumenical & Interfaith, Faith & Worship

Tags: ali, christian-muslim relations, dialog, interfaith, islamic, louisville, memorial, muhammad, muslim

Ministries: Theology, Formation & Evangelism