‘Our kids are somebodies’

By Cindy Cushman | Presbyterians Today

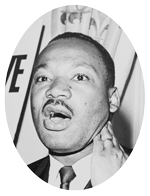

“I would like to suggest some of the things that you must do and some of the things that all of us must do in order to be truly free. Now the first thing that we must do is to develop within ourselves a deep sense of somebodiness. Don’t let anybody make you feel that you are nobody. Because the minute one feels that way, he is incapable of rising to his full maturity as a person. … Now this is all I’m saying this morning, that we must feel that we count. That we belong. That we are persons. That we are children of the living God. And it means that we go down in our soul and find that somebodiness and we must never again be ashamed of ourselves. We must never be ashamed of our heritage. We must not be ashamed of the color of our skin. Black is as beautiful as any color and we must believe it.” — Martin Luther King Jr.

“I would like to suggest some of the things that you must do and some of the things that all of us must do in order to be truly free. Now the first thing that we must do is to develop within ourselves a deep sense of somebodiness. Don’t let anybody make you feel that you are nobody. Because the minute one feels that way, he is incapable of rising to his full maturity as a person. … Now this is all I’m saying this morning, that we must feel that we count. That we belong. That we are persons. That we are children of the living God. And it means that we go down in our soul and find that somebodiness and we must never again be ashamed of ourselves. We must never be ashamed of our heritage. We must not be ashamed of the color of our skin. Black is as beautiful as any color and we must believe it.” — Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. spoke these words at Glenville High School in Cleveland on April 26, 1967. Several things have happened that have had me mulling on this concept of “somebodiness” and how, 50 years later, MLK’s words here are still so strikingly relevant.

The officer who shot and killed Philando Castile was acquitted of all charges in Castile’s death. An Ohio judge declared a mistrial for the second time in the trial of Ray Tensing, the University of Cincinnati police officer who shot and killed Samuel DuBose. Twelve-year-old Tamir Rice was shot and killed by an officer — who never faced criminal charges — in Cleveland. Rice would have been 15 years old this year.

My youngest sons — African-American twins we adopted from foster care when they were toddlers — are six months older than Tamir Rice. That makes them nearly old enough to begin driving in Kentucky, where we live. I’ve been thinking about the fact that even though we have given our boys “the talk” numerous times about how to behave when stopped by police, it didn’t help Philando Castile, who did everything we’ve told our boys to do and still wound up dead.

I’ve been thinking about how, as younger, more naïve white parents of young black children, we banned toy guns because of our opposition to gun violence, not because of how a police officer might respond to a toy gun in the hands of a black child. It took a few personal experiences of seeing how others stripped our sons’ “somebodiness” from them to fully understand this reality.

Once, we sat in a meeting at school and listened to the principal dismiss our then-4-year-old son’s chances of success because “he’s a drug baby.” When his brother was 10, he accidentally stepped on the toe of a parent at a soccer game when he was trying to save a ball from going out of bounds. He apologized immediately yet was derided by that parent as a “stupid little black boy.”

Cindy Cushman’s experience raising children of different ethnicities has given her an understanding of the challenges her African-American sons face. Courtesy of Cindy Cushman

Last year one of them was with a group of black friends in a supermarket, buying drinks after playing basketball, and they were stopped by the manager and accused of stealing — not because they were stealing or even bothering anyone, but because a group of five black teenage boys is seen as a threat.

So I’ve been thinking about King’s concept of somebodiness. I’ve been thinking about how no matter how much black Americans throughout these past 50 years have heeded MLK’s words to develop “a deep sense of somebodiness,” black bodies will continue to be unjustly killed until white America does some deep thinking on this concept as well.

All God’s children

As a Presbyterian pastor, I want to call on my white Christian friends to look at this concept of somebodiness through the lens of our faith and consider what it really means to honor the somebodiness of our black brothers and sisters.

MLK said in the speech, “We must feel that we count. That we belong. That we are persons. That we are children of the living God.” With that statement, King makes a claim, rightly, that black people, every bit as much as white people — and all other people of color as well — are indeed children of the living God. We as Christians are called to honor the somebodiness of all God’s children.

From the creation of humanity in God’s image (Genesis 1:26–27) to the prophetic vision of God’s diverse kingdom (Isaiah 2:2) to Jesus’ notion of love and justice for all, God’s love of all kinds of people shows up again and again in the Bible. Time and time again Jesus encounters people whose somebodiness has been diminished — lepers, children, the woman at the well and others. All have been diminished by other people.

As Christians, we are called to honor the somebodiness of all God’s children, just as Jesus did. Part of doing so is acknowledging that their somebodiness, like our own, is not dependent on their behavior or any of their personal characteristics. In the wake of the acquittal of Philando Castile’s killer, the King Center tweeted, “Extol #PhilandoCastile’s virtues, but know: Even if he didn’t serve children, even if he didn’t love his family, he should still be alive.”

True to the person the King Center represents, this tweet reminds us that the value of Castile’s life, his somebodiness, was not rooted in his actions, but in the fact that he was a child of the living God. He was somebody in God’s eyes, somebody whose life mattered to God, and somebody whose life must matter to us.

We white Christians hopefully have no trouble affirming this truth. But what we may have more difficulty with is acknowledging that society as a whole does not operate in such a way that this truth is lived out on a daily basis.

Confronting my white privilege

The fact is that racism exists, as does white privilege. Some bodies still matter more than other bodies. From the time slaves were brought into this country as property, we as a nation have diminished the somebodiness of black people in this country. I’ve seen it happen to my children.

I know many “good Christian white folk” who continue to deny the reality of white privilege. And to a degree, I get it. It’s not that they don’t care, or that they’re being dismissive, but they have trouble wrapping their mind around the concept that they are privileged.

White privilege is being able to take our “somebodiness” for granted. We are treated as “somebody” pretty much everywhere we go. But that is not the case for everyone. And that is especially not the case for black Americans.

Keeshan Harley was a 21-year-old college student in New York City when Soledad O’Brien interviewed him for a CNN special series she did called “Black and Blue.” Keeshan had never been in trouble, never committed a single crime, nor been charged with one. He was — and presumably still is — a good kid, working on getting his college degree. But when O’Brien interviewed him in 2014, he had been stopped and frisked more than 100 times. More than 100 times he went through this, before the NYPD’s stop-and-frisk policies were scaled back in 2015 — even though he’s never done anything wrong. Because of the neighborhood he lives in. Because he has black skin.

He talks about the humiliation of being told by police officers to put his hands against the wall, getting patted down as people are walking by, staring. More than 100 times he has gone through this — even though he’s never done anything wrong.

Imagine how those repeated experiences of being stopped by police would affect your sense of somebodiness. Especially when we factor in a recent Stanford University study in Oakland, California, that found that police officers were likely to speak to white community members more respectfully than to black community members.

We white Americans have the privilege of being able to expect that when we are stopped by police, the officer will speak to us with respect and not overreact out of fear when we make movements to follow their instructions to get out our license and registration. We expect to be able to move through the world around us without having to worry about such things, without having to even think about them. Our somebodiness is taken for granted, by others and by ourselves.

But for so many black Americans, each time they struggle, accidentally step on toes, go to a grocery store or are stopped by police, they face the possibility, and perhaps even the likelihood, that their somebodiness will be stripped away from them just a little bit more.

They don’t have the privilege of being looked at and seen as an individual person. Instead, they are looked at and seen as a category or possible criminal.

Not having to worry about an occasional lapse in good behavior is white privilege. Going grocery shopping with friends without being harassed is white privilege. Simply driving without being stopped is white privilege.

We must stop refusing to talk about racism and privilege simply because it makes us uncomfortable. Our feelings of discomfort are less important to God than whether a black person lives or dies. God doesn’t value white somebodiness over black somebodiness.

And the more that good, white Christian folk refuse to address racism — in ourselves and in society — the more that black lives will continue to be taken unjustly.

As Christians, we cannot in good faith say, “I don’t need to worry about that because it doesn’t affect me.” If it affects another person who is somebody in God’s eyes — and let us not forget that all people are somebody in God’s eyes — then as a Christian, it affects me.

If we want our lives to have ultimate significance, we are called to honor and lift up the somebodiness of all of God’s people. When we do so, we live out our own somebodiness to its fullest potential, honoring ourselves, the other and especially God.

Cindy Cushman is the organizing pastor of the Southern Hills Parish in Ohio Valley Presbytery. She and her husband, Kerry Rice, are the parents of six children, four of whom were adopted from foster care.

![]() You may freely reuse and distribute this article in its entirety for non-commercial purposes in any medium. Please include author attribution, photography credits, and a link to the original article. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDeratives 4.0 International License.

You may freely reuse and distribute this article in its entirety for non-commercial purposes in any medium. Please include author attribution, photography credits, and a link to the original article. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDeratives 4.0 International License.

Categories: Presbyterians Today, Racial Justice

Tags: antiracism, facing racism, Martin Luther King Jr, philando castile, racial justice, racism, somebodiness, tamir rice, white privilege

Ministries: Presbyterians Today, Gender, Racial and Intercultural Justice, Racial Equity & Women’s Intercultural Ministries