A Letter from Jhanderys and Ian Vellenga, serving in Nicaragua

February 2019

Write to Ian Vellenga

Write to Jhanderys Dotel-Vellenga

Individuals: Give online to E200391 for Ian and Jhanderys Dotel-Vellenga’s sending and support

Congregations: Give to D507593 for Ian and Jhanderys Dotel-Vellenga’s sending and support

Churches are asked to send donations through your congregation’s normal receiving site (this is usually your presbytery).

After months of waiting, we finally arrived in Nicaragua on January 22. Typically, people like to think that getting up and moving to another country is as easy as it sounds. Just grab your suitcase, your passport, your wallet, and you’re off. It took us a little longer than that, but we finally made it. There is a certain romantic notion of packing a few things and living on a tropical island sipping piña coladas and sleeping in hammocks all day at the beach (especially during the winter months). For us, the most difficult part about moving was deciding what to take and how to pack our stuff. We don’t own a lot, but we were a little clueless about how to pack while staying below the airline baggage weight limit. And then there are the other required things, like health check-ups, some financial planning, and handling all the paperwork that comes with moving to another country. We also needed to find a place to live, and luckily, within the first week of our arrival we were able to rent a small house close to where we work. Now we are in the process of getting the required furniture for our new place: fridge, stove, TV, beds, couches, dishes, etc. But we are slowly getting there.

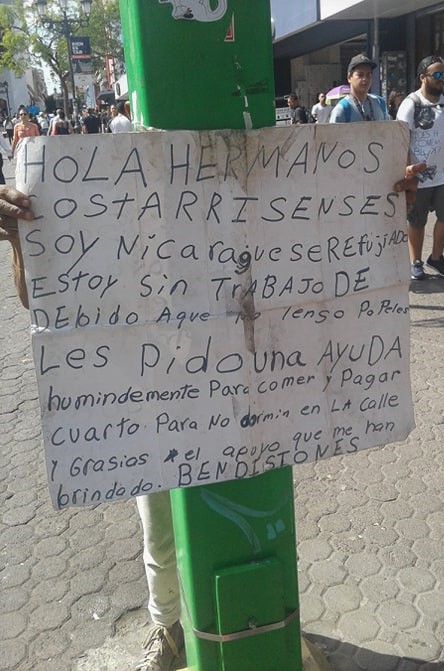

We moved to Nicaragua voluntarily, willingly and happily — because of our jobs, because we have a sense of calling, and because we want to experience life together in a different country. But we are not the only ones moving to another place. People leave their home countries for various reasons: some to experience other cultures, some to pursue job opportunities, some to retire to an “exotic” place (whatever that means). But for so many others, moving to another country is not easy, voluntary, or pleasurable. Some move and become refugees to escape hardships due to conflicts and war in their countries; some move to escape persecution due to their beliefs, political affiliation, sexual orientation, gender, or ethnic identities; some migrate for a chance to improve their living conditions, to provide a better quality of life for themselves and for their loved ones; and some move just to be able to stay alive. Thousands of people migrate every year, for different reasons, all with the hope or expectation of improving their lives economically, physically, emotionally, and spiritually.

Stories about people moving and migrating across borders have become a staple of cable news and most mainstream media in the last couple of years, with dramatic shots of people crossing borders (especially the stock footage of crossing between the United States and Mexico) featured on various news channels. In cases like ours, people are expecting you and happy to receive you; there’s food and a bed waiting; you feel safe, protected and valued; people treat you with politeness, consideration and respect. Migration, in this case, is a satisfactory experience that is shared by migrant(s) and the host nation or individuals. But in many cases, the experience of those migrating is all but uncomplicated and painless. In fact, it can be complex, mournful, detrimental and life-threatening. Migrants come from many countries and places. Frequently, migrants are forced to leave their nations and communities due to widespread and endemic violence: they move for reasons beyond their control in search of safety and well-being. But often they are discriminated against by the country they are migrating to due to their nationality, economic status, language, geographical location, way of entry, and cultural identity.

We as privileged migrants (in the sense of choice, reasons, and conditions) mostly fail to understand the hardships and distress that moving away from home, family, friends and everything that is familiar and known can cause to those seeking asylum and refuge. We often focus more on how they enter the country, educational level, and economic means than on the things they are escaping or trying to leave behind. We in many ways choose to ignore their humanity, rights, and needs. We mute their pleas, and we ban and criminalize them when a life with dignity, safety, and freedom is all they are searching for.Words and prayers are no longer enough. We need more than just empathy in the search for peace and justice. What is needed are effective actions to change laws and behaviors that sustain systematic discrimination and promote hate towards the other. How can we be oblivious to the effects of anti-immigration laws in the United States, Europe, and many other places when we ourselves are migrants? We need to stop the discourse that promotes the idea that some migrants are acceptable while others are not. We need to promote awareness of the circumstances that force people to leave their communities and societies behind at the risk of even losing their own lives. Yes, laws are complicated and the global and local economies are challenging, but rejection, separation, and incarceration do not fix the problems that bring migrants to our borders and shorelines in the first place. Consciousness; understanding; challenging and changing arbitrary laws and policies that traditionally exclude some and favor others; and focusing on real humane treatment and a responsible international community are some of the things that can really make a difference. Let’s not just sit, watch, and pray about it. Let us contribute to the necessary changes to allow all human beings to live with the dignity that God has intended for all.

We appreciate all of your prayers, encouragement and financial support. Please continue in your support for our ministry, and please keep us as well as CEPAD and Nicaragua in your prayers.

Jhan and Ian

![]() You may freely reuse and distribute this article in its entirety for non-commercial purposes in any medium. Please include author attribution, photography credits, and a link to the original article. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDeratives 4.0 International License.

You may freely reuse and distribute this article in its entirety for non-commercial purposes in any medium. Please include author attribution, photography credits, and a link to the original article. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDeratives 4.0 International License.