A Letter from Bob and Kristi Rice, serving in South Sudan

Spring 2021

Write to Bob Rice

Write to Kristi Rice

Individuals: Give to E200429 for Bob and Kristi Rice’s sending and support

Congregations: Give to D507528 for Bob and Kristi Rice’s sending and support

Churches are asked to send donations through your congregation’s normal receiving site (this is usually your presbytery)

Subscribe to our co-worker letters

Dear friends,

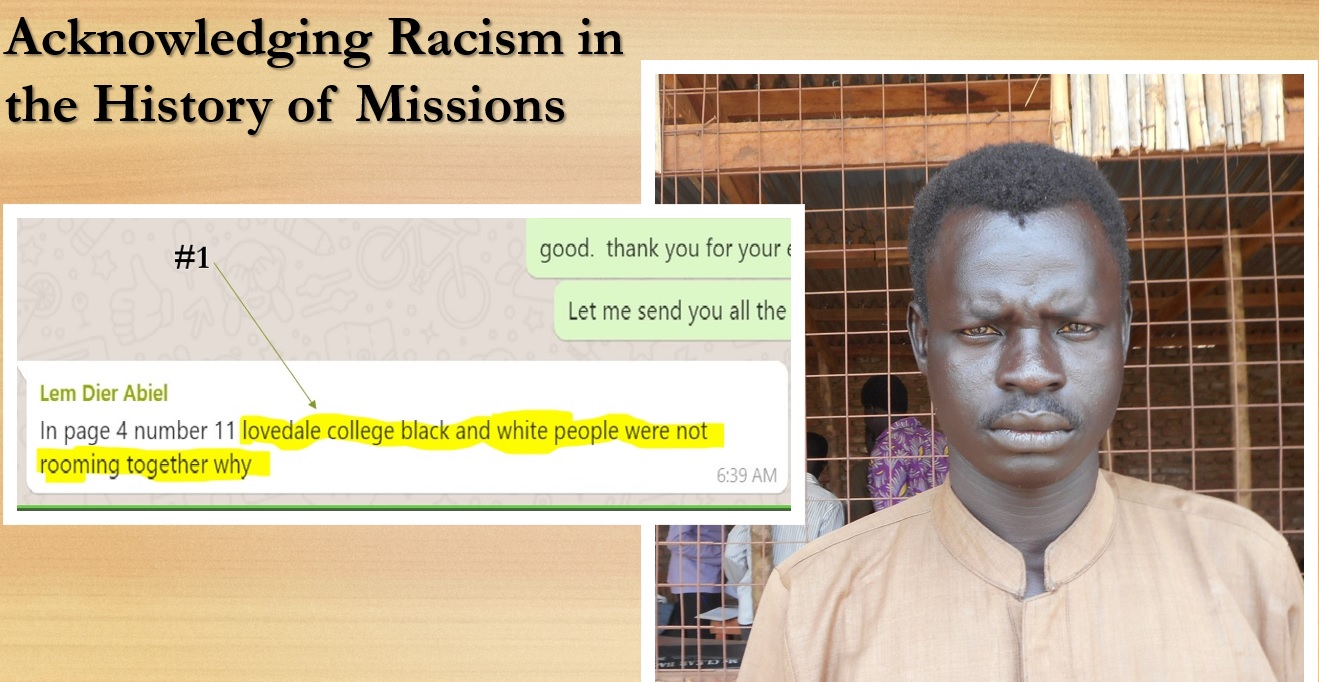

Last year I taught an online course called African Church History for my students in Juba. It was a wonderful learning experience. During our time exploring the history of mission and the church in South Africa, we learned about the establishment of Lovedale College in 1841, an institution which trained catechists and evangelists. As a matter of practice during this course, after listening to lecture clips which I sent to students via WhatsApp, students would then respond in the chat box with comments and questions. Lem Dier Abiel, one of my students, from the lecture and the lecture notes wrote this message in the chat box, “In page 4 number 11 lovedale college black and white people were not rooming together why.” Lem’s honest and incisive question stopped us in our tracks. Why did the school choose to separate students? Why were the Black South African students and the white students not rooming together? Why were these students not permitted to do all of life together?

Lem’s question and the realities in South Africa behind his question betray an important theme from the African Church History course, the theme of racism in the history of Christian missions in Africa. While we are good at celebrating the positive and glamorous stories of mission, we often leave the shadow side unspoken. We default to the “epistemology of forgetting.” We convince ours6elves that the good stories are the whole story. Yet how can we be made whole if we do not tell the bad stories, allow these stories to inform us, and reform us? Leaning into and not neglecting the discomfort of the shadow side of mission, our shared stories can lead us into the deeper landscape of who we are and who we need to become, issuing possibilities towards repentance, healing, reconciliation, and personal and communal wholeness.

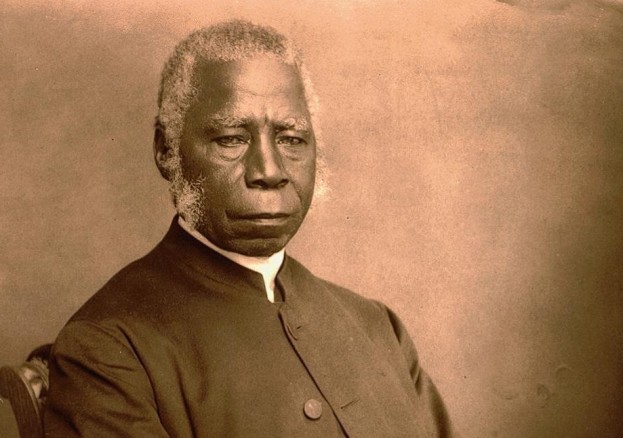

Samuel Ajayi Crowther is described by one historian as “one of the greatest and most lovable personalities in nineteenth-century African Church history.” Crowther became Sierra Leone’s first African Anglican priest and later became Africa’s first Anglican bishop. Empowered by the famous missionary statesman Henry Venn, Crowther served as the head of the Niger Mission. He was appointed to supervise an impossibly large region that today comprises modern-day Nigeria. Crowther was a capable leader, finding creative ways to support this extensive mission.Tragically, Crowther’s efforts were undermined by young, ambitious missionaries from England. These European missionaries of the 19th century believed themselves superior to their African counterparts. They, along with European traders who pursued “ruthless capitalism” in their business ventures, found ways to circumvent and delegitimize the leadership of Crowther. Thus, Bishop Crowther was divested of his administrative power and influence.

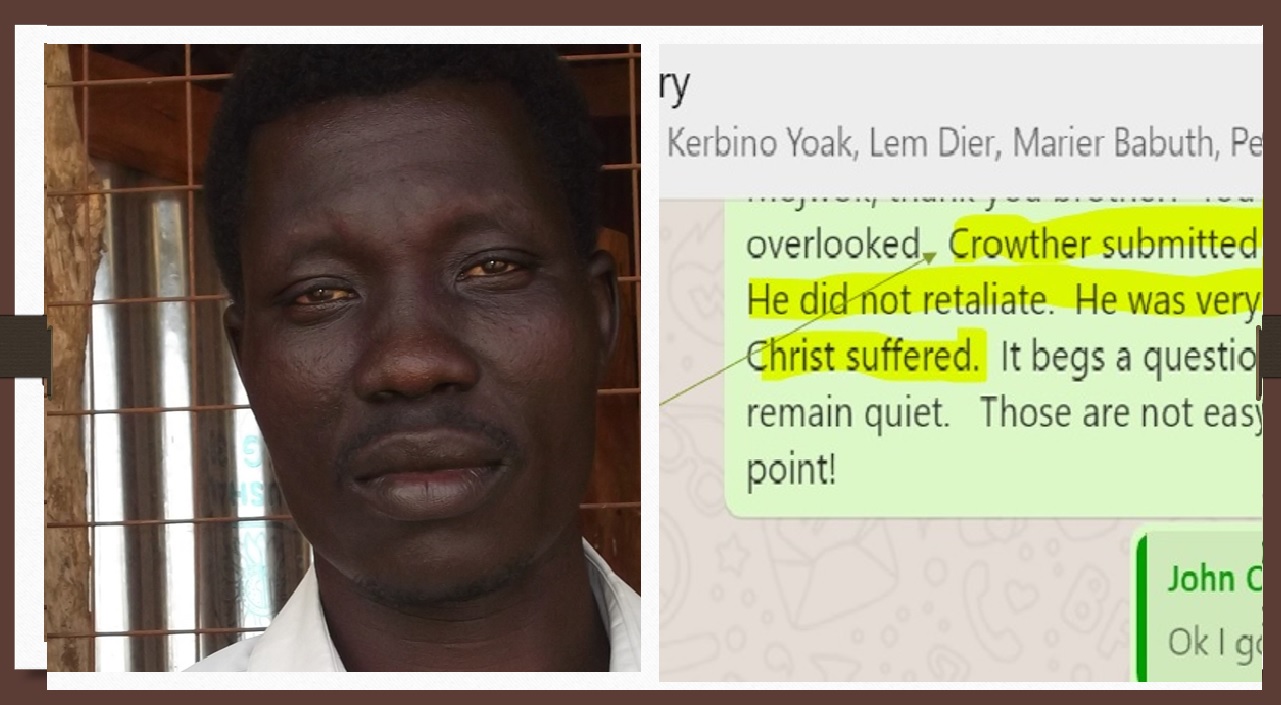

John Ohdong, one of my students, affirmed Crowther for not retaliating, for suffering as Christ suffered. Yet, the injustice perpetrated against our African brother remains troubling. While the Church would later vindicate Bishop Crowther, this situation and subsequent events elucidate racist beliefs held by missionaries of the 19th century in Africa. Missionaries, in almost every situation, did not support or entrust leadership to their African brothers and sisters. I am grateful for students like Lem and John who have been willing to engage me regarding the distressing legacy of racism in the history of Christian mission.

Recently, Kristi and I have joined colleagues across the Presbyterian Mission Agency in learning more about diversity, equity, and inclusion. Alongside colleagues serving in Africa and other parts of the world, including those living and serving here in the United States, we have heard startling truths and realities which we might choose to turn away from. Investigating the shadow side of our church, our mission history, and our continued mission engagement is unpleasant. As we look at the legacy of colonialism in Africa and the complex relationship between colonialism and Christian mission, it is not difficult to see the harm brought to the peoples of Africa. One colleague described it as the “colonial wound.” Our facilitator in our equity training described the legacy of colonialism as “peanut butter residue.” While we want to forget about this negative colonial history and our complicity with it, thus distancing ourselves from it, as with peanut butter in an empty jar, the smell and feel of it remains whether we like it or not. The sins of yesterday become part of our shared story today.

As the Presbyterian Mission Agency, we are currently taking a hard look in the mirror. As we have sat and listened to one another, racism in its pernicious and unexamined expressions continues to impact how we relate to one another, and it continues to compromise our witness in the world. Collectively, we have a lot of work to do in naming and acknowledging racism and discovering how to live out our faith in ways that clearly reflect the justice and mercy of God. We aim to build a future together, to be and to become the Beloved Community to which Christ has called us, demonstrating Gospel values of equity, mutuality, humility, sacrifice, justice, and love. Please pray with us in this process as we address and repent from the “peanut butter residue” of colonialism, white supremacy, and racism.

Thank you for standing with us as we stand with partners and friends in South Sudan. Please pray with us for our return to South Sudan, hopefully in the not-too-distant future.

Love,

Bob and Kristi

![]() You may freely reuse and distribute this article in its entirety for non-commercial purposes in any medium. Please include author attribution, photography credits, and a link to the original article. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDeratives 4.0 International License.

You may freely reuse and distribute this article in its entirety for non-commercial purposes in any medium. Please include author attribution, photography credits, and a link to the original article. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDeratives 4.0 International License.