A letter from Karla Koll, serving in Costa Rica

November 2017

Write to Karla Ann Koll

Individuals: Give online to E200373 for Karla Ann Koll’s sending and support

Congregations: Give to D506645 for Karla Ann Koll’s sending and support

Churches are asked to send donations through your congregation’s normal receiving site (this is usually your presbytery).

Advent has come again to remind us that we have not yet arrived. Advent calls us from our daily tasks to focus on our expectations and hopes for the future. As such, Advent is eschatological time.

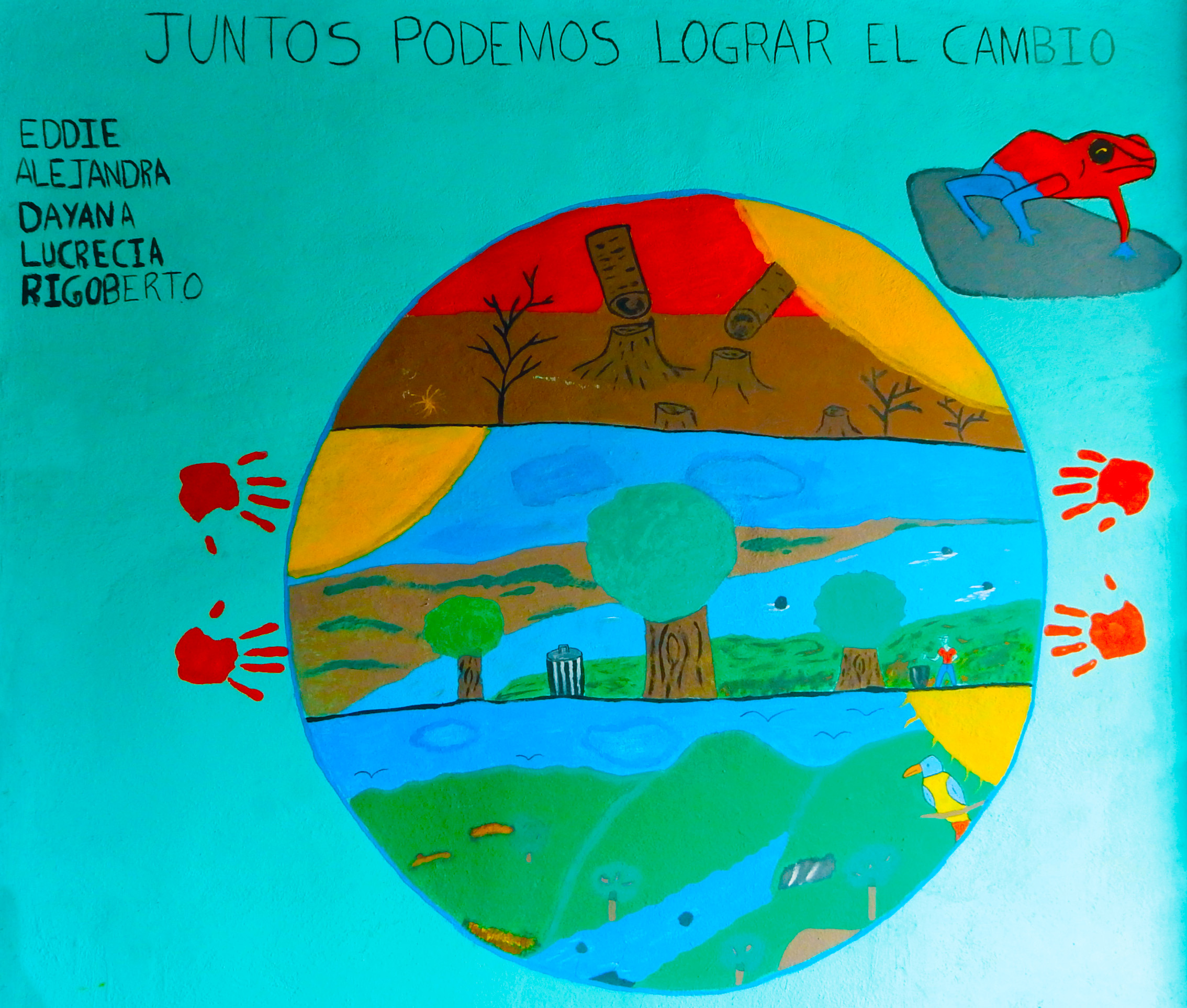

This Advent, a group of students and I at the Latin American Biblical University (UBL) are exploring eschatology in times of climate change. Eschatology is that area of theology that focuses on our expectations for the future and destiny of all of creation. The 2017 Atlantic hurricane season brought unprecedented levels of devastation by storms made more intense by warmer ocean water temperatures. Here in Costa Rica, eleven deaths were reported as Tropical Storm Nate formed off the Caribbean coast and began its trek north to become a hurricane. Here, as elsewhere, the effects of climate change are already being felt.

In this part of the world, preachers in many churches, as well as on radio and television, are quick to interpret the disasters caused by weather phenomena as God’s punishment for sin or as signs that the end times predicted by a certain reading of biblical texts are fast approaching. Thus the vulnerable communities that are bearing the brunt of the effects of climate change are seen either as the guilty who deserve God’s wrath or as collateral damage in a cosmic scheme. At the UBL, we offer a different vision.

Advent encourages us to take our clues about what we expect in the future from what God has done in the past. John’s gospel puts it this way: “The Word became flesh and lived among us” (John 1:14). In the incarnation, God takes on a fully human life, lived out in a particular time and place. Like every other human being, Jesus lived within and depended upon a local ecosystem, one that had been degraded centuries earlier by deforestation. Jesus invited people to look to the birds of the air and the flowers of the field, sustained by the ongoing ecological processes, as models for human life. To take the incarnation seriously is to focus on the ecosystem in which we are living out our faith in the God of Jesus.

Recently, the UBL published a translation and adaption of an introduction to Watershed Discipleship by the biblical scholar Ched Myers. Wherever we live, our place is defined by a larger system called a watershed in which all living beings are linked by a shared water course. Watershed discipleship is an invitation to rethink our theology and practice of our faith within the topography of creation.

Throughout the Americas, communities are organizing to protect water sources. In August, a travel study seminar focused on peacemaking, climate justice and faith brought eleven people from the United States to Central America to listen to the stories of these communities. This travel study seminar was organized by the Peacemaking Program and Environmental Ministries of the Presbyterian Church (USA). During a week in Guatemala, the group visited indigenous communities that are resisting the El Tambor gold mine and the El Escobal silver mine. These communities face continual repression, criminalization and violence as they defend their land and water through non-violent actions.

Given Costa Rica’s international reputation as an ecological paradise, the group did not expect to encounter communities whose water sources are being threatened. We traveled to Milano, a community not far from the Caribbean coast, where chemicals used in the nearby pineapple plantations have rendered the local water supply unfit for human consumption. Costa Rica is now the world’s leading exporter of pineapples. For the last ten years, the rural aqueduct association responsible for providing potable water to the 350 households in Milano has had to bring in water trucks two or three times a week. Neither the government nor the pineapple companies have taken responsibility for cleaning up and protecting the communities’ water supply, despite the communities’ ongoing legal efforts.

The UBL is located in the watershed of the Torres River, a tributary of the Tarcoles River, one of the most polluted rivers in Central America. At the beginning of November, my students and I participated in a workday to clean up a stretch of the river bank. On that Saturday morning, a group of several dozen volunteers pulled over two tons of plastic, cloth and metal from the river and its banks. Because of our efforts that day, perhaps less plastic found its way to the Pacific Ocean. Yet we also know that the river won’t be clean until this society ceases to generate so much trash. As Ernesto Padilla, a student from Peru, commented, working to clean the river means working to clean our own lives and our own lifestyles.

The UBL is living its commitment to planetary life in other ways as well. In 2018, we will be turning part of our property into a community garden with the support of the municipal government. We have also joined the Green Seminary Initiative, a three-year certification process to integrate creation care and climate justice into all areas of our community and institutional life.

As Advent begins a new liturgical year, I give thanks for all of the gifts and prayers that make it possible for me to be part of training church and community leaders here at the Latin American Biblical University. Presbyterian World Mission and I hope that you will continue to support my work here in Costa Rica with these women and men who are committed to serving their communities, working for justice and healing the ecosystems where they live.

Wishing you Christmas joy,

Karla

![]() You may freely reuse and distribute this article in its entirety for non-commercial purposes in any medium. Please include author attribution, photography credits, and a link to the original article. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDeratives 4.0 International License.

You may freely reuse and distribute this article in its entirety for non-commercial purposes in any medium. Please include author attribution, photography credits, and a link to the original article. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDeratives 4.0 International License.