A Letter from Joseph Russ, serving in the Northern Triangle of Central America

Fall 2022

Write to Joseph Russ

Individuals: Give to E132192 in honor of Joseph Russ’ ministry

Congregations: Give to D500115 in honor of Joseph Russ’ ministry

Churches are asked to send donations through your congregation’s normal receiving site (this is usually your presbytery)

Subscribe to my co-worker letters

Dear friends,

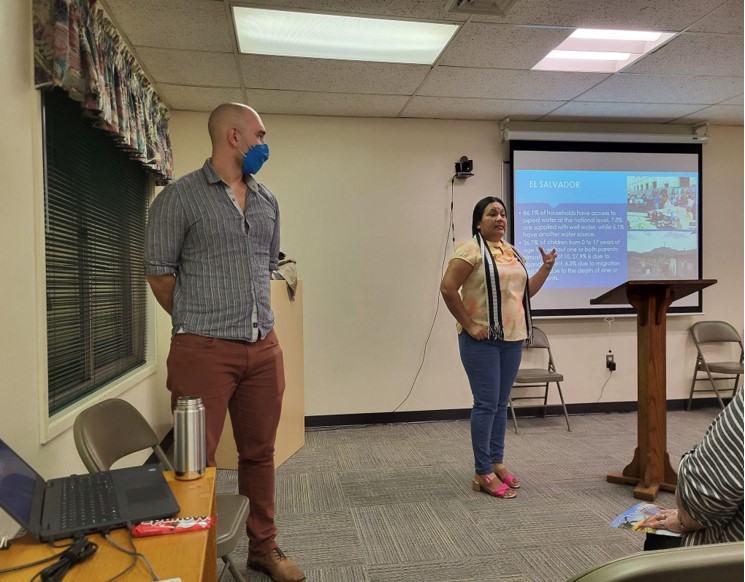

This past month, I interpreted for my colleague Carmen Díaz from the Reformed Calvinist Church of El Salvador while traveling in the U.S. through the PC(USA) Peacemaking Program.

Over the past six years living in El Salvador, I have helped people visiting El Salvador understand the history, culture and stories that might be unfamiliar to them. By doing so I helped them try to make sense of another country, context and world, and helped them avoid offending someone or causing problems for partners in El Salvador.

I found myself doing something similar for Carmen while sharing about my own culture, country and history.When we have the opportunity to share about our world, we reflect on our own world. What makes our culture and history special? Interesting? Problematic?

It’s a chance to learn more about ourselves and the cultural forces that have shaped us and our world.

* * *

When in Richmond, Virginia, we toured the places where statues of Civil War generals had been torn down. We talked about the Civil War in the 1800s, but seeing Confederate flags still flown in parts of the country, we needed to explain why people still fly a flag from a rebellion that failed over 150 years ago. Why were so many statues of generals from this war erected in the 1960s and 1970s so long after this conflict was over? The ugly sides of our history, and the way these dynamics continue today, had to be explained.

But we also shared stories of resistance to the celebration of these figures. We talked about protestors and activists who advocated for the tearing down of these statues, who speak out against racism today, or who physically removed these statues, even tossing a statue of Cristopher Columbus into the river. Because the history of the U.S. isn’t just the history of oppression, but also the history of resistance to this same oppression. It is the history of the struggle for liberation.

* * *

At a museum in Kansas, we saw a display of a big U.S. American flag and the words “Thank you for your service.” Like a good interpreter I translated it into Spanish, but Carmen asked, “Who are they thanking? Whose service? Is this like doctors and nurses? Teachers?”

And it dawned on me with a sense of sadness that it wouldn’t even occur to me to think of a sign like this as a reference to teachers or medical professionals. Because being raised in the U.S. we understand that the most important people to thank for their service are military personnel.

And Carmen was shocked.

Part of this is because a mere 40 years ago, Salvadoran death squads and military battalions (many of whom were trained in and equipped by the U.S. military) were massacring civilians and murdering activists.

I was shocked too. Now, whether or not you believe that serving in the military is a noble thing to do, I do believe it says something tragic about our values that this is what we esteem above all else. Our country is so deeply dedicated to militarism and war that the default we think of in the context of gratitude and service is almost always in reference to those people and armaments dedicated to killing other people.

From the beautiful and inspiring stories of resistance to the harrowing stories of oppression and jingoism, there is something to learn from all of it. All these stories help us understand ourselves and understand one another.

* * *

When I worked receiving groups for human rights education programs, one of our documents for foreigners broke down things about El Salvador to help them adjust.

- Put used toilet paper in a trash can (not the toilet).

- Wear bug spray for the mosquitos.

- People in El Salvador tend to be polite and avoid confrontation, so don’t confront people directly and be extra polite.

Some of these are logistical details and suggestions for dealing with the material differences people may encounter. But others are reflections on cultural tendencies and these can be reductive.

By handing out a document lumping together “cultural differences” with material advice about what to do with toilet paper, are we subtly essentializing cultural differences with the same concrete certainty of one correct way to dispose of toilet paper?

Telling someone from the U.S. that “You need to understand Salvadoran culture” subtly implies that during a one-week visit, “You CAN understand Salvadoran culture.” It requires that another culture be reduced to an object of understanding to be grasped, but not a reflection on one’s own self, world or culture.

* * *

What if, instead of explaining Salvadoran culture to foreigners, we asked foreigners to reflect on their own culture? What if we asked people:

- “What does politeness mean to you? Rudeness?”

- “Do you prefer direct communication, or roundabout communication?”

- “What does it mean to be ‘on time’?”

As we reflect on this, we ourselves realize that when we are in another place, we may find that people have VERY different responses to these questions. Just because something seems rude to us does not mean that it is rude to them. That just because it is different doesn’t mean it’s wrong.

Interculturality is about understanding ourselves better, so we don’t make the mistake of assuming others are “wrong.” It helps us reflect on the ways we “be” in the world. And not only does this help us have better intercultural interactions and challenge our egotism, but it also actually helps us understand ourselves.

Reflecting on our own culture, we may find that our own imagination and thriving has been limited by oppression, racism, colonialism, militarism, et cetera. We find that the only way to find liberation for others is to work for liberation together.

Joseph

La Beleza del Aprendizaje Intercultural

Otoño 2022

Queridas amigas y amigos,

Durante el mes pasado, interpreté para mi colega Carmen Díaz de la Iglesia Calvinista Reformada de El Salvador mientras viajaba por los EE. UU. a través del Programa de Construcción de Paz de PC (EE. UU.).

Durante los últimos seis años viviendo en El Salvador, he ayudado a las personas que visitan El Salvador a comprender la historia, la cultura y las historias que pueden no ser familiares para ellos. Les ayudó a tratar de dar sentido a otro país, contexto y mundo. Les ayudó a evitar ofender a alguien o causar problemas a los socios en El Salvador.

Y me encontré haciendo algo similar para Carmen. Compartir sobre mi propia cultura, país e historia.

Cuando tenemos la oportunidad de compartir sobre nuestro mundo, reflexionamos sobre nuestro propio mundo. ¿Qué hace que nuestra cultura e historia sean especiales? ¿Interesantes? ¿Problemáticas?

Es una oportunidad de aprender más sobre nosotros mismos y las fuerzas culturales que nos han dado forma a nosotros y a nuestro mundo.

* * *

Cuando estuvimos en Richmond, Virginia, recorrimos los lugares donde se habían derribado las estatuas de los generales sureños de la Guerra Civil. Hablamos de la Guerra Civil en la década de 1800, pero al ver que las banderas confederadas aún ondean en partes del país, necesitábamos explicar por qué la gente todavía ondea una bandera de una rebelión que fracasó hace más de 150 años. ¿Por qué se erigieron tantas estatuas de generales de esta guerra en las décadas de 1960 y 1970, tanto tiempo después de este conflicto? Los lados feos de nuestra historia y la forma en que estas dinámicas continúan hoy.

Pero también compartimos historias de resistencia a la celebración de estas figuras. Manifestantes y activistas que abogaron por el derribo de estas estatuas, que se pronuncian hoy en contra del racismo, o que físicamente retiraron estas estatuas, incluso arrojando una estatua de Cristóbal Colón al río. Porque la historia de los EE. UU. no es solo la historia de la opresión, sino también la historia de la resistencia a esta misma opresión. La historia de la lucha por la liberación.

* * *

En un museo en Kansas, vimos una exhibición de una gran bandera estadounidense y las palabras “Gracias por su servicio”. Como buen intérprete lo traduje al español, pero Carmen preguntó: “¿A quién le están dando las gracias? ¿El servicio de quién? ¿Esto es como médicos y enfermeras? ¿Maestros?

Y me di cuenta con una sensación de tristeza de que ni siquiera se me ocurriría pensar en un letrero como este como una referencia a maestros o profesionales médicos. Debido a que nos criamos en los EE. UU., entendemos que las personas más importantes a las que agradecer por su servicio son el personal militar.

Y Carmen se sorprendió.

Parte de esto se debe a que hace apenas 40 años, los escuadrones de la muerte y los batallones militares salvadoreños (muchos de los cuales fueron entrenados y equipados por el ejército de los EE. UU.) masacraban a civiles y asesinaban a activistas.

Yo también estaba impactado. Ahora, ya sea que crea o no que servir en el ejército es algo noble, creo que dice algo trágico sobre nuestros valores que esto es lo que estimamos por encima de todo. Nuestro país está tan profundamente dedicado al militarismo y la guerra que lo que pensamos por defecto en el contexto de la gratitud y el servicio es casi siempre en referencia a aquellas personas y armamentos dedicados a matar a otras personas.

Desde las bellas e inspiradoras historias de resistencia hasta las desgarradoras historias de opresión y jingoísmo, hay algo que aprender de todo ello. Algo que nos ayude a entendernos a nosotros mismos y a entendernos unos a otros.

* * *

Cuando trabajaba recibiendo grupos para programas de educación en derechos humanos, uno de nuestros documentos para extranjeros desglosó cosas sobre El Salvador para ayudarlos a adaptarse.

Ponga el papel higiénico usado en un bote de basura (no en la taza).

Use repelente de insectos para los zancudos.

La gente en El Salvador tiende a ser cortés y evita la confrontación, así que no

confrontes a la gente directamente y sé extra cortés.

Algunos de estos son detalles logísticos y sugerencias para lidiar con las diferencias materiales que las personas pueden encontrar. Pero otros son reflejos de tendencias culturales. Y estos pueden ser reductivos.

Al entregar un documento que agrupa las “diferencias culturales” con consejos materiales sobre qué hacer con el papel higiénico, ¿estamos esencializando sutilmente las diferencias culturales con la misma certeza concreta de una forma correcta de desechar el papel higiénico?

Decirle a alguien de los EE. UU. que “Tienes que entender la cultura salvadoreña” implica sutilmente que durante una visita de una semana, “PUEDES entender la cultura salvadoreña”. Requiere que otra cultura se reduzca a un objeto de comprensión para ser captado, pero no un reflejo sobre uno mismo, el mundo o la cultura.

* * *

¿Qué pasaría si, en lugar de explicar la cultura salvadoreña a los extranjeros, les pidiéramos a los extranjeros que reflexionaran sobre su propia cultura? ¿Qué pasa si le preguntamos a la gente:

“¿Qué significa la cortesía para ti? ¿Grosería?”

“¿Prefieres la comunicación directa o la comunicación indirecta?”

“¿Qué significa estar ‘a tiempo’?”

Al reflexionar sobre esto, nos damos cuenta de que cuando estamos en otro lugar, podemos encontrar que las personas tienen respuestas MUY diferentes a estas preguntas. El hecho de que algo nos parezca grosero a nosotros no significa que sea grosero con ellos. Que solo porque sea diferente no significa que esté mal.

La interculturalidad trata de comprendernos mejor a nosotros mismos para no cometer el error de asumir que las demás personas están “equivocadas”. Nos ayuda a reflexionar sobre las formas en que “ser” en el mundo. Y esto no solo nos ayuda a tener mejores interacciones interculturales y a desafiar nuestro egoísmo, sino que en realidad nos ayuda a entendernos a nosotros mismos.

Reflexionando sobre nuestra propia cultura, podemos encontrar que nuestra propia imaginación y prosperidad ha sido limitada por la opresión, el racismo, el colonialismo, el militarismo, etcétera. Vemos que la única forma de encontrar la liberación para los demás es trabajar juntos por la liberación.

Joseph

Please read the following letter from Rev. Mienda Uriarte, acting director of World Mission:

Dear Partners in God’s Mission,

What an amazing journey we’re on together! Our call to be a Matthew 25 denomination has challenged us in so many ways to lean into new ways of reaching out. As we take on the responsibilities of dismantling systemic racism, eradicating the root causes of poverty and engaging in congregational vitality, we find that the Spirit of God is indeed moving throughout World Mission. Of course, the past two years have also been hard for so many as we’ve ventured through another year of the pandemic, been confronted with racism, wars and the heart wrenching toll of natural disasters. And yet, rather than succumb to the darkness, we are called to shine the light of Christ by doing justice, loving kindness and walking humbly with God.

We are so grateful that you are on this journey as well. Your commitment enables mission co-workers around the world to accompany partners and share in so many expressions of the transformative work being done in Christ’s name. Thank you for your partnership, prayers and contributions to their ministries.

We hope you will continue to support World Mission in all the ways you are able:

Give – Consider making a year-end financial contribution for the sending and support of our mission personnel (E132192). This unified fund supports the work of all our mission co-workers as they accompany global partners in their life-giving work. Gifts can also be made “in honor of” a specific mission co-worker – just include their name on the memo line.

Pray – Include PC(USA) mission personnel and global partners in your daily prayers. If you would like to order prayer cards as a visual reminder of those for whom you are praying, please contact Cindy Rubin (cynthia.rubin@pcusa.org; 800-728-7228, ext. 5065).

Act – Invite a mission co-worker to visit your congregation either virtually or in person. Contact mission.live@pcusa.org to make a request or email the mission co-worker directly. Email addresses are listed on Mission Connections profile pages. Visit pcusa.org/missionconnections to search by last name.

Thank you for your consideration! We appreciate your faithfulness to God’s mission through the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.).

Prayerfully,

Rev. Mienda Uriarte, Acting Director

World Mission

Presbyterian Mission Agency

Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.)

To give, please visit https://bit.ly/22MC-YE.

For it is the God who said, ‘Let light shine out of darkness,’ who has shone in our hearts to give the light of the knowledge of the glory of God in the face of Jesus Christ. 2 Corinthians 4:6

![]() You may freely reuse and distribute this article in its entirety for non-commercial purposes in any medium. Please include author attribution, photography credits, and a link to the original article. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDeratives 4.0 International License.

You may freely reuse and distribute this article in its entirety for non-commercial purposes in any medium. Please include author attribution, photography credits, and a link to the original article. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDeratives 4.0 International License.