A Letter from Joseph Russ, serving in the Northern Triangle of Central America

Summer 2023

Write to Joseph Russ

Individuals: Give online to E132192 in honor of Joseph Russ’ ministry

Congregations: Give to D500115 in honor of Joseph Russ’ ministry

Churches are asked to send donations through your congregation’s normal receiving site (this is usually your presbytery)

Subscribe to my co-worker letters

Dear friends,

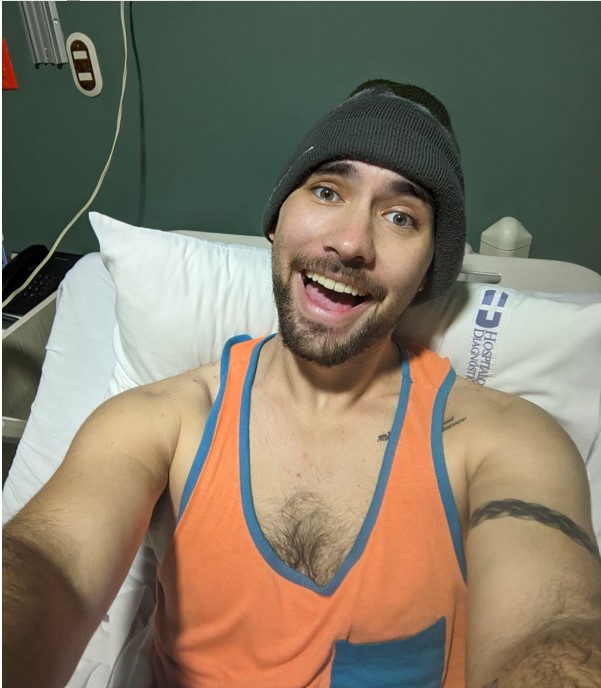

Let me preface this newsletter by saying: I’m fine now. Totally fine and living life to the fullest.

Some people already know that I got seriously ill in February. A case of tonsillitis didn’t respond to antibiotics until my tonsil swelled up and almost closed my throat. In the hospital with an IV, the swelling went down, and I had my tonsils removed, but healing after the surgery took longer than expected.

A week later, I felt a pain in my side, went back to the hospital, and was diagnosed with tuberculosis. There were large abscesses on my lungs and the additional tests confirmed it was TB. Nowadays, tuberculosis is pretty uncommon and very treatable. It’s really only common in prisons, where people lack access to the health care necessary to treat it. I did feel like garbage for a while, and I needed to isolate for a few weeks while we began treatment.

Coincidentally, I was later diagnosed with gout and rheumatoid arthritis and started treatment in May.

The point is, I was pretty sick for a few months.

—

I was lucky to have friends and family from around the world that reached out to me when they heard I was sick. People were kind and offered to get me food or cook or send memes. My parents even offered to fly down and take care of me.People also had lots of recommendations about what to do. One person told me to take fewer showers. Another told me to go find an herb that grows in the forests of El Salvador and brew it into a special tea. Everyone wanted to help.

But there are also cultural dimensions to illness. I wasn’t just sick I was sick in El Salvador with my Salvadoran friends. That means my treatment is covered by the state. It also means a lot of people reached out to help. Eight people offered to go shopping for me, come over, or cook. One of my good friends had to fend off other people who wanted to come to cook me food when I’d said I didn’t want any. People wanted to show support and were not shy about doing so.

My parents were distraught, but they asked if they should come to visit me, and when I said, “no,” they stopped asking. My aunt wrote me a couple of times and even asked if it was okay to check on me again.

In general, more people who wrote to me from the U.S. assumed I might want to be left alone or that they should ask before trying to do things for me. In general, more people in El Salvador assumed I would need things done for me and it was out of my own stubbornness that I tried to do it on my own. If not for my friend intervening, people might have just shown up unannounced at my house with food.

And they were part right. I am stubborn. I don’t like to ask for help. My own reaction to my illness has a lot to do with my own culture, gender, ability and other parts of my identity.

Obviously, these are generalizations in one short newsletter. But I think they point to a greater idea: our cultural upbringing informs the ways we respond to illness.

—

Healing the unwell was one of Jesus’s major concerns. It’s clear that improving the health and lives of the sick is a Christian response. Jesus allowed the sick to touch him physically, breaking purity rules of the day. From the woman with the bent back to the paralytic man to the many people dealing with leprosy, Jesus was a person who listened to the sick, was in community with the sick, gave them what they needed and healed the sick.

But listening to the sick means we also seek to heal and help in culturally relevant ways. Rather than ask ourselves, we can ask those we care for how best to care for them. When engaged in ministry abroad, we can ask those we support what health looks like for them, what role the community plays, who is most vulnerable and how to improve access to healthcare.

I am truly fortunate that the kind of community that prayed for my health and included me even virtually when I couldn’t be in person. I am fortunate to have a community that cared for me in the best ways they can, and a community that cared for me in the ways I wanted to be cared for.

Joseph

![]() You may freely reuse and distribute this article in its entirety for non-commercial purposes in any medium. Please include author attribution, photography credits, and a link to the original article. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDeratives 4.0 International License.

You may freely reuse and distribute this article in its entirety for non-commercial purposes in any medium. Please include author attribution, photography credits, and a link to the original article. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDeratives 4.0 International License.